Against the background of an ongoing onslaught on the University’s gender-minority colleges, we seek to explore what it means to exist in DU’s so-called ‘safe spaces’ and why any threat to their sanctity must be dealt with the gravity of an ‘invasion’.

Introducing yourself as the student of a women’s college is an act that elicits a wide range of responses. From blatant objectification of yourself and your peers as ‘dream girlfriend material’ to feigned concerns about how the institutional absence of men is hindering your ‘holistic’ development, it is evident that gender-minority spaces are no safe haven from patriarchy. If anything, patriarchy operates in covert ways within and outside the walls of these institutions.

Beyond sexist stereotyping and disparaging remarks, it manifests as the very real and physical threat of gender-based violence, of which these students often become primary targets. As our campus witnesses a rise in public displays of male entitlement and territorial chauvinism, it is imperative that we learn to contextualise these incidents and understand that no violation of a safe space happens in isolation.

Before delving into the subject of gender-minority spaces and what threatens them, it is crucial to understand what these spaces symbolise for their students in the first place. The very need for exclusive spaces for women and gender minorities points to a history of sexual violence that has endangered these groups for simply existing in public. Delhi itself hosts the track record of being one of the most unsafe metropolitan cities for women in the country, with the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) recording 14,277 registered cases of crimes against women in the Union Territory in 2021 alone. The fear of violence is thus statistically backed up and deeply embedded in the collective psyche of gender-minority groups, who are forced to live much of their lives on ‘survival mode’.

In the midst of an overwhelming threat to life and autonomy, gender-minority spaces emerge as a cocoon of safety for historically marginalised groups. Hence, Priya Agrawal, a student of the Indraprastha College for Women (IPCW), Delhi University’s (DU) oldest women’s college established in 1924, comments,

There is a reason why our parents and relatives feel very comfortable with the fact that their daughter is in an all-girls’ college. They feel that she’ll be safe there.

In fact, this dichotomy between unsafe public spaces and the safe space of gender-minority colleges is epitomised by the daily experience of commuting to the latter. Any student of these institutions is all too familiar with the sense of relief that rushes over you as soon as you step inside your college gates and are no longer bound to check the length of your skirt or feel the gaze of a man staring down your chest. As Sobhana, a student of Miranda House, relates,

The journey from my house in Vijayanagar to the Miranda House campus, which is no longer than 3 minutes by rickshaw or 10 if you walk, gives me more trauma and catcalls than the entire day I spend on campus.

It is apparent why, despite the conflictual nature of the inner workings of these colleges, they hold sanctity as a form of ‘private space in public’ universities (to borrow author Shelly Tara’s idiom, who used it originally in the context of women-only coaches on the Delhi Metro).

All of this is not to paint gender-minority colleges as infallible institutions above any and all forms of discrimination. Caste, class, religion, queerness, and other social cleavages dictate the inner anatomy of these institutions, and indeed, the very notion of a ‘safe space’ comes to be contested in the face of social hierarchies and exclusionary cliques. Any sense of safety is accorded on the basis of privilege and it is crucial that we keep this intersectional standpoint at the back of our minds while examining the remainder of this issue.

So, it is not the case that DU’s gender-minority colleges represent some sort of progressive, feminist utopia, but more so that they unite students under the banner of shared experience and solidarity against patriarchal injustice. Payal Krishnan, an LSR alumna from the batch of 1996, says,

Even in a women’s institution, you would routinely face instances of internalised misogyny and homophobia, and it takes time and dedicated efforts to shatter. Just stepping inside a women’s institution doesn’t automatically make you a certain way. But luckily, we always had people come out in support of individuals and communities which were discriminated against, and that unwavering support and dedication towards creating a safe space is what mattered.

Despite the numerous problems that permeate such institutions, she speaks of a “culture of cooperation, respect, and holistic growth” and concludes, “There is power in the collective.” This power—this collective front put up against the omnipresent violence of gender norms—is what poses an existential threat to patriarchy. While it is not within the scope of this article to delve into the rich history of these colleges, it is true that dominant society has always felt a sense of unease in the presence of such highly-educated and liberated women. Whether it be the 1990s matrimonial ads declaring ‘Girls from JNU, LSR or Miranda House need not apply’ or the aforementioned judgemental remarks, the autonomy of gender-minority spaces has always existed as an open challenge to the hetero-patriarchal foundations of our society.

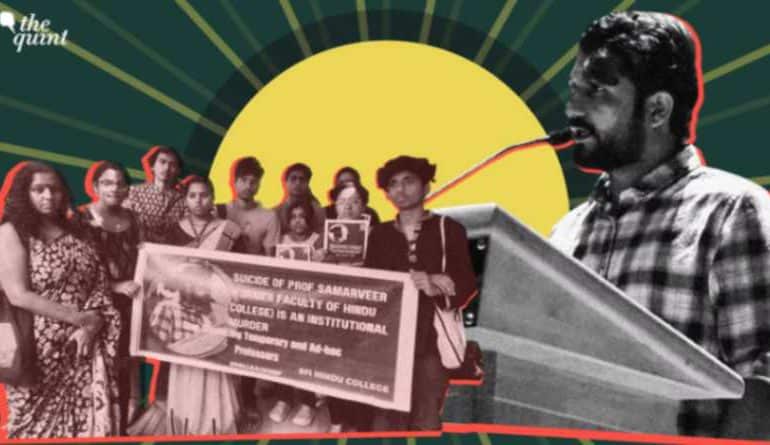

Perhaps it is this challenge, this daring not to conform, that has resulted in the repeated targeting of these spaces and attempts to infringe upon their boundaries. Case in point is that of the recent DUSU election campaigning rallies that have barged into women-only campuses, but also of much earlier incidents, such as the 2020 Gargi College fest, the 2022 Miranda House Diwali mela, and the 2023 IPCW fest. It is evident that these are not isolated incidents but rather a pattern of invasions that legitimises male entitlement to spaces clearly not meant for them. Even relatively normalised behaviours, such as men deliberately hanging around outside women’s college gates, are not to be dismissed either, since they form the root of this very patriarchal problem of ‘space and who occupies it’.

The cases of women’s college fests being invaded by men are some of the most publicized events within this scenario. These incidents, which become grounds for rampant sexual harassment in the form of catcalling, groping, and unwanted advances, and actively put the students’ safety at risk, have been meticulously covered by national media houses as well. What is often left out of the conversation, however, is the aftermath of such events. Sharing her traumatic experience during the IPCW fest invasion and how that permanently changed her perception of the college environment, one student relates,

The purity of the place was gone for me. I did not go to college for 1-2 weeks straight because there were many protests, but also because I didn’t feel like it. Many of my friends didn’t go either. Even months after, as soon as we’d enter, we’d get flashbacks from that night.

It should be made clear then that men climbing walls and trying to barge into gender-minority spaces are not a case of them doing just that. These are incidents that reinstate the fear of violence and re-establish the norm of male proprietorship over women and gender minorities. They serve as a painful reminder to the latter that no space that they construct with love and care for themselves is truly theirs forever. It is forever dangling under the threat of patriarchal violence and could be overcome, at any moment, by the ever-destructive male ego. As the above-quoted IPCW student went on to share,

Even after all this went down, people still don’t realise that this was not about a college having a concert, where people simply climbed the walls and chaos and stampede happened. No, it’s not about that. It’s about men trying to enter the space of women, trying to harass us in our own spaces, and telling us, ‘We can come here too; what will you do about it? Your administration is not going to help you out either.

Indeed, it is only within this context that one can begin to understand the visceral reaction of gender-minority students against their spaces being invaded. Recently, when the political rallies for the DUSU 2023 elections barged into Aditi Mahavidyalya and Miranda House, students of both colleges were quick to label these as ‘invasions’ and expressed dissent against them. Unfortunately, they were dismissed under the claim that such hooliganism is just ‘part and parcel’ of the DUSU election fever. Such statements, that ring too close to the common adage of ‘boys will be boys’, fundamentally fail to understand the sanctity that safe spaces hold for gender minorities and the reason why they might get so protective about them.

It is no far-fetched remark to also suggest that the way elections season has panned out over the past month in DU has been nothing but a display of power under patriarchy. Yes, money and muscle power reign supreme in this University’s (and by large, the country’s) electoral politics, but must we be so quick to accept that as the norm, as students and conscious voters? Must we allow our gender-minority spaces to be violated for the sake of more noise and pamphlet-litter? Of course, one also wonders why it is always the same political outfits, like ABVP and NSUI, that choose to engage in this chauvinist brand of student politics. Perhaps, someone will tell us to quietly accept that just as boys will be boys, ABVP and NSUI too will be ABVP and NSUI.

Ultimately, what matters, however, is the safety of our spaces. One of the most disheartening outcomes is always the immediate reaction of administrative authorities, who seem quicker to police the gender-minority students than take action against the perpetrators. Whether it be barbed wire being put up on college walls or student protestors being detained before the men who invaded IPCW, the question of who will protect our safe spaces remains unanswered.

Read also: The Invasion of IPCW – A Student’s Account

Featured Image Credits: Anshika for DU Beat

Sanika Singh

[email protected]