As you think of others far away, think of yourself (say, “If only I were a candle in the dark”). –Mahmoud Darwish (translated by Mohammed Shaheen)

At the time of writing this article, it has been 40 days since the commencement of Israel’s relentless retaliatory assault on the Palestinian people living in Gaza and the Occupied West Bank. Following the Hamas attack on October 7, 2023, Israel’s offensive has resulted in the tragic deaths of at least 11,000 Palestinian civilians, with over 20,000 sustaining injuries. 42 journalists and media workers have lost their lives, and the war has recorded the highest number of UN aid worker casualties in the history of the organisation. Craig Mokhiber, the former Director of the New York Office of UNHCR, who resigned in protest of the United Nations’ failure to intervene and avert the crisis, has described the unfolding humanitarian catastrophe as “a textbook case of genocide.” Yet, if one were to turn to mainstream media, particularly in the West, one would find a very different picture than this grim reality.

Indeed, the Western reporting of the Israel-Palestine issue has been marred by a series of “erroneous Western assumptions,” as Professor Amir Ali of the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) called them in a commentary piece for the Economic and Political Weekly. From an ahistorical account of the situation as beginning on October 7, 2023, to the labelling of all condemnations of Israel’s actions as antisemitism, along with the ad-nauseum repetition of “Do you condemn Hamas?” Prof. Ali identifies these assumptions as reflective of “the moral and intellectual bankruptcy of the West.” Underneath these apparent fallacies in logic, of course, lie much more deliberate and coercive forces of racism, Islamophobia, and the state-driven race for geopolitical gains.

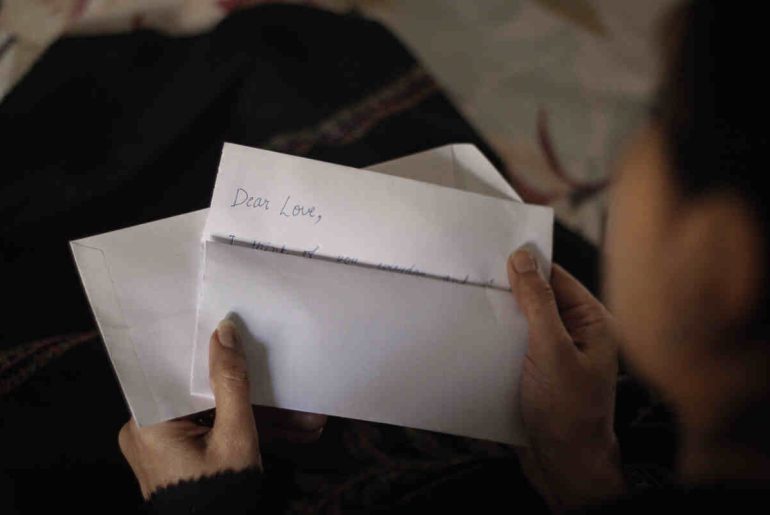

In light of this active epistemic erasure, many have chosen to turn instead to Palestinian journalists, photographers, and activists, such as Plestia Alaqad, Bisan, Yara Eid, and Ali Jadallah, among others, who have utilised their social media presence to document the harrowing genocide as it unfolds on the ground. “My photos travelled the world, but my feet couldn’t touch my homeland,” reads the Instagram bio of Motaz Azaiza, one such Gaza-based photojournalist, whose photographs have indeed travelled the digital world and exposed the ongoing atrocities of the Israeli state. From highly graphic and excruciating images of dead or injured children to capturing the daily resilience of the Palestinian people, the social media posts of Gazan civilians like Motaz have struck the consciences of millions across the world. Amid active attempts to dehumanise victims of genocide, they have served as an unprecedented tool of personal documentation, humanising the statistics too often reduced to mere death tolls.

The democratisation of information dissemination via social media has brought out the face of a genocide like never before in history. Such is the power of online discourse that many experts have called it “a battle to control the narrative dimensions of conflict and war.” The meddling forces in this narrative battle include disinformation, online propaganda, and censorship by social media platforms. The latter is particularly pertinent in the current context, as numerous activists, journalists, and regular users have accused major platforms of shadowbanning or taking down Palestine-related content. Yet, the sheer magnitude of this online movement is evident in the fact that October saw 15 times more posts on Instagram and TikTok with pro-Palestinian hashtags than pro-Israeli ones, as reported by Humanz, an influencer marketing company founded by former IDF intelligence officers.

On an individual scale, this has translated to what I’d like to term ‘digital-user morality’ for the purposes of this article. Digital-user morality may be understood as a form of individual social responsibility that encourages the socio-politically conscious usage of one’s social media platform, however big or small, to create awareness about issues that matter. Emphasising the complicit nature of silence and ignorance, it calls upon individuals to speak out for what’s right and stand in solidarity with marginalised communities across the world.

The idea here is not to suggest that passive engagement in the form of a single repost or retweet is going to bring about a revolution. Rather, the objective is to harness online support and channel it into tangible forms of dissent and protest movements. With the widespread adoption of the BDS (Boycott, Divest from, and Sanction) movement and people marching in the thousands across the world, it is evident that the line between digital activism and real-world mobilisation is a thin one, and the former has a significant bearing on public sentiment about war.

As we continue to mobilise our voices for Palestine, it is also crucial to be cognizant of the pitfalls of virality and not forget the many ‘silent genocides’ unfolding in other parts of the world right now, such as the Congo and Sudan. Social media is a powerful tool, but it is a tool based on capital, after all. So, when the Palestine issue inevitably dies out its so-called time on social media, just as the Manipur issue did earlier this year and countless other humanitarian crises that seldom see the spotlight, remember not to let your activism be washed away in the transient waves of online attention.

Read Also: What’s Going on in Gaza and Why You Should Care

Image credit: @motaz_azaiza on Instagram

Sanika Singh

[email protected]