Securing admission to Delhi University feels like a dream come true for people from different Cultural, social, economic, and political backgrounds. Education thus becomes a channel to uplift themselves. However, the reality with the landlord mafia is far stretched.

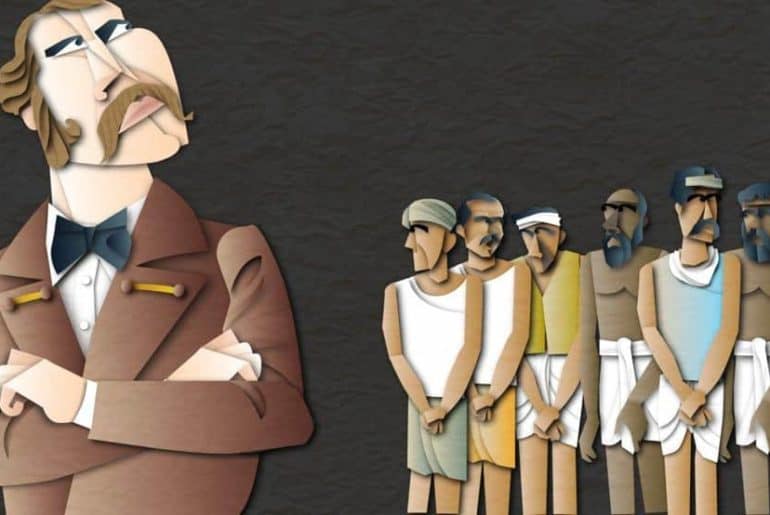

Securing admission to Delhi University feels like a dream come true for people from different Cultural, social, economic, and political backgrounds. Education thus becomes a channel to uplift themselves. However, the reality is far stretched. Students in and around the area of North Campus have often raised concerns related to their accommodation and the high rent prices by the landlords. There have been frequent complaints about the quality of services these PG owners provide. Even then the landlord mafia which controls the chain of accommodation continues to have their way out. The brokers and landowners have been time and again propagating social and regional Discrimination. In such a scenario no structure acts as a system of checks and balances on the ethical aspect of these issues.

At present, the University Campus has witnessed several political changes, one of them which includes the saffronization of our academic spaces. The minority communities around the University campus are the most neglected and side-lined. Nuzra Tafzeel, a 3rd year student in DU from Lucknow says,

It has been almost 2 years living here. When my sister and I were looking for a flat, every broker said, “Hum Muslim ladkiyon ko flat nahi dete” (we don’t give flats to Muslim girls).”

Nuzra recounts how so many of her other friends got flat in the area but she couldn’t.

Landlords and brokers both equally bluntly deny any Muslim person to rent their flat.”

Furthermore, this shows how polarized the campus has now become. People hailing from the Northeast often face hurdles in getting a flat where the owners don’t allow them to cook non-vegetarian food.

The landlord didn’t spare my previous flatmate. She hails from Manipur and last year when the ethnic strife unleashed Manipur she couldn’t contact her home and get the money. The owner was understanding for a month but then kept bothering her a lot.” – Srijeeta who has completed her master’s from the University of Delhi.

A week ago, I came across a broker’s WhatsApp status which said, “Haryana people nothing is available as of now” (exact words via a prominent broker’s WhatsApp status). In terms of geographical context, people from regions like Haryana, the Northeast, and Kerala face the brunt of such lewd stereotypes and majority of these owners refuse to rent out their flats to people hailing from these regions.

All of this doesn’t function in itself, it also has its roots in the lack of providing infrastructure facilities. Especially in cases when Hostel accommodation hasn’t witnessed any increase in seat allocations in the past few years.

Of the 20 DU colleges offering hostel facilities (till 2019), six offer both male and female hostels, while 12 colleges offer only female hostels and the rest offer only male hostels.” – Kainat Sarfaraz for Hindustan Times

The flawed administration leaves countless students stranded and helpless. Elected representatives in Delhi University Students’ Union (DUSU) elections make false promises to secure votes, which often remain unfulfilled. Most of the candidates who contested for DUSU Union Elections (2024-25) did not address this issue in their campaigns either.

Another prominent issue that comes up in the University Campus area is harassment and abuse by these brokers and PG owners and their attitude toward female students. Many women have encountered brokers who have tried to ask uneasy questions and drunk texted them at odd hours like late at night. Suhani (name changed for privacy concerns) said,

Our PG owner pretended to be unmarried and lured a 1st-year girl into a relationship with him.”

Students also spoke about scams they had encountered through these brokers who took the security amount but did not enter into any contract or agreement. Unnati Verma, a second-year student from Miranda House who hails from Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, recounts how she was scammed by someone who pretended to be a broker.

I lost 65 thousand rupees to this. The flat was nothing like what they had shown through the videos online. On top of this, the broker abused me and my family. Ultimately, we decided to not rent the flat from him.”

For students like Unnati who have a limited budget for their accommodation, these instances not only deprive them financially, but also affect their mental well-being. Beneath the romanticisation of the North campus is a multi-layered reality of misogyny, social hierarchy, religion-based discrimination, and harassment. As the academic year 2024-25 approaches its halfway point, severe action against such individuals is required to ensure that no further students fall victim to such brokers.

Read Also: Fire Break-Out and Violation of Bylaws: All in One for Mukherjee Nagar PGs

Featured Image Credits: Jyotsna Singh

Jyotsna Singh