Prof. G.N. Saibaba did not ‘pass away’ on 12th October 2024. He was gradually and brutally murdered by the state, the Indian academia, and our collective silence. The Indian university has become a graveyard, with students and academics being executed for voicing their opinions. Is staying silent the best that we are capable of?

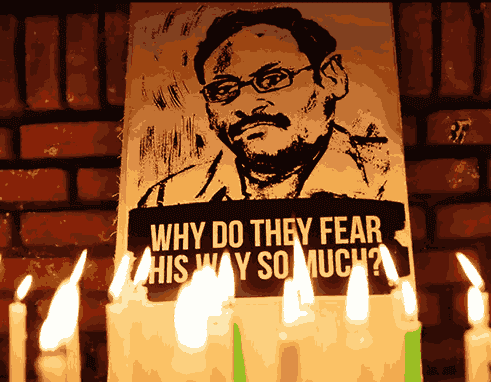

The first time I came across G.N. Saibaba was in a social media post from 2022 that dealt with his ongoing case and featured the poem ‘I Refuse to Die’ from the collection of his prison poetry and letters, Why Do You Fear My Ways So Much? The poem and his case prompted me to buy the book and read more about him. G.N. Saibaba was the first poet I read after getting admitted to the literature program at the University of Delhi in 2022, and I carried the text with me to my first lecture in college only in the hope that someone would recognise it. The text became my first introduction to the oppression that the DU administration and the state are capable of meting out to a 90% disabled professor, even before I physically reached my college. It was only a matter of a few months before I would witness academic precarity firsthand in my department when my professors would be displaced, and later, Prof. Samarveer Singh of Hindu College would be forced to take his life.

G.N. Saibaba’s death is simultaneously, both a rare case of UAPA in which each institution of the state and even the university administration worked in tandem with each other but led to Saibaba’s eventual bail and also another case of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) imposed on the academic-activist on no solid grounds, except for his alleged “links with the banned Maoist party.”

Though the BJP-led government has made significant amendments to the UAPA and excessively imposed it on students, academics, and activists to curb any criticism of the state in the last decade, it is important to note that the draconian law was imposed on Saibaba by the Congress-led UPA government in 2012. The misuse of the colonial era law by the UPA government, a part of which today stands as an alternative and the opposition to the NDA alliance, allowed the exploitation of the law and for it to be made arbitrary by the latter, to the extent that the law was amended to shift the burden of proof from the accuser, usually the state, to the accused, making bails in such cases extremely rare.

Though Saibaba was granted bail, he was not even allowed to visit his mother’s funeral and was physically tortured by the prison authorities during his abduction-cum-arrest from DU campus and in jail that led to the paralysis of his left arm, denied basic healthcare facilities, and even contracted the coronavirus twice while he was in jail. Despite all of these grave concerns, Saibaba was continuously denied bail, even though several high profile individuals were given bail during the pandemic. When he was finally acquitted in October 2022 by the Division Bench of the Bombay High Court, the Maharashtra government filed a petition and challenged the HC’s order at the Supreme Court, and on the very next day, Saturday 15th October 2022, a special bench of the SC comprising Justice Bela Trivedi and Justice M.R. Shah stayed the HC’s acquittal order, citing how the “brain is the most dangerous and integral part of committing terrorism-related offences”.

The profiling of progressive academics, activists, and intellectuals as ‘terrorists’ has been made into a common practice by the state and the university administrations have also been actively complicit in this. It is alleged that a colleague of Saibaba at the Ram Lal Anand College was responsible for helping the state frame him in the case. Prof. Saibaba was also unfairly terminated from his job as an assistant professor at Ram Lal Anand College, DU even before he was proved guilty in the case.

This atmosphere of fear and surveillance in the saffronised university space has not only been responsible for the death of several intellectuals but has also been actively used by the state to break networks of solidarity—in the case of Prof. Hany Babu who was a part of the defence committee for Saibaba and has also been incarcerated under UAPA. Even the lawyer Surendra Gadling who fought the case for Saibaba’s release was charged with UAPA and the judges who had acquitted Saibaba have faced consequences for the same.

In conversation with DU Beat at a memorial organised for Saibaba, Professor Jenny Rowena, wife of Hany Babu, said,

We always talk about issues when somebody dies, then it becomes a viral thing. We saw Rohith Vemula when he was alive. How much attention do we give to these people? Even now, people who are in jail because they campaigned for Saibaba, like Hany Babu, Rona Wilson, and Surendra Gadling, who was their lawyer, are still in jail. These people also have a lot of health problems, so are we waiting for the same to happen to them? We all should really protest against UAPA. All condolence meetings that we have should also be against UAPA. There should be a mass movement against it, because they [the state] are using it ruthlessly now to crush any kind of opposition and dissent.”

The law has been reduced to a tool of state repression and is being increasingly used to arrest students, young activists, academics and other intellectuals who criticise the state under the garb of ‘national security’ and by labelling them as terrorists. Not only is it absurd that young students and 90% disabled professors are labelled as ‘terrorists’ and potential ‘threat to the nation’ but it is against the constitutional values that promote critical and free thinking. In fact the very structured and systematic manner in which each institution of the state and each public institution including the universities and the media is working in complicity with the state to corner dissenters is in itself a symptom of a regime of terror that the UAPA supposedly seeks to counter.

It is also important to take into cognizance the notions of ‘terrorism’ that UAPA seems to be against. Is fighting for the rights of Adivasis and against their killings terrorism? Is peacefully opposing state operations such as Operation Green Hunt and Operation Samadhan an act of terrorism?

Is mere ‘links with Maoist organisations’, as Saibaba was accused of, or ‘possession of Marxist literature’ terrorism? If yes, do students of the humanities and social sciences, particularly literature and history, who study Marxism as a compulsory part of their course, pose a threat to the nation and are terrorists? Does mere engagement with or belief in a particular ideology that may or may not be critical of the state’s beliefs, constitute as terrorism? Today, even asking these questions can lead to the imposition of a UAPA case. In fact, academics who have worked on such topics for their PhDs are often harassed by prestigious academics and labelled as anti-national in job interviews.

The law is being increasingly used to destroy public universities by imprisoning students such as Umar Khalid, Gulfisha Fatima, and Sharjeel Imam, among hundreds of other students for peacefully protesting against divisive laws, an undeniable law of each citizen. The incarceration of these students under UAPA have also been orchestrated so as to ‘set an example’ for dissenting students and to silence them, developing a disquiet culture of suppression and destroying the culture of resistance that India’s public universities have been known for.

The constant ‘red-flagging’ of individuals who identify with the Left or are in opposition to the state policy and may or may not identify with the Left, in conjunction with the profiling of individuals as “urban naxals” by state authorities, including the Prime Minister, not only qualifies as discrimination on the basis of ideas and leads to connotations of anti-state and anti-national individuals, but also leads to anti-intellectualism that has been identified as one of the most important factors behind the development of a fascist state.

Though the judges at the Supreme Court have been citing how “bail is the rule and jail is the exception”, it does not seem to apply to UAPA cases, more than half of which are not being investigated, as per the National Crime Records Bureau. In Saibaba’s murder and the human right violations as a part of it, the state did not merely attempt, though unsuccessfully, to kill his ideas but also take away his life, as it did with Father Stan Swamy, Pandu Narote, and SAR Geelani. By unfairly terminating his contract with the university, it was ensured that Saibaba does not get to teach his students ever again and one of his most heartfelt desires to teach students after being released from prison, was left unfulfilled. As Saibaba remarked in one of his letters to his students and colleagues from the prison:

I hope none of you should feel sympathetic to my condition. I don’t believe in sympathy; I only believe in solidarity. I intended to tell you my story only because I believe that it is also your story. Also because I believe my freedom is your freedom.”

Even in solitary confinement, his desire for freedom was not restricted to himself. The campaign against him was not only unfair to him but also his family and also his students, who were not allowed to be taught by a brilliant scholar, teacher, and translator whose translations of Kabir have been the most significant and timely in English so far.

Though we have been reduced to observing birthdays, death anniversaries, and anniversaries of arrests of activists and students as they remain incarcerated without trials and more than a handful of unsuccessful hearings, the outrage at the murder of Prof. G.N. Saibaba is both a culmination of our complicity in his murder and simultaneously a rupture in the amnesia surrounding state repression under UAPA. That should pave the way for a movement against UAPA and the larger culture of saffronisation-infused anti-intellectualism. For the message should be clear: the state should not and cannot kill ideas, let alone individuals. As Saibaba himself claimed and rightly so, he and his ideas and struggles refuse to be forgotten and to die..

Read Also: DU Collective comes together in solidarity and remembrance of Professor G.N. Saibaba

Featured Image Credits: Shahid Tantray’s Instagram

Vedant Nagrani