Old Delhi has always held a majestic charm because of its unique food culture, which dates back centuries. In this article, we magnify Mughlai cuisine lovers’ favourite destination, Karim’s.

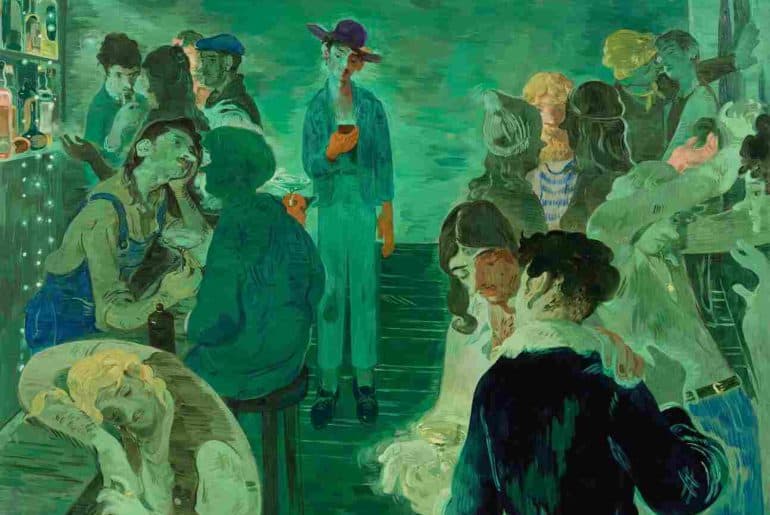

In 1857, when the British won over the Indian mutiny and ended the Mughal rule of Bahadur Shah Zafar in India, several royal cooks from the Mughal kitchen became unemployed. To sustain themselves, they set up food stalls around the streets of Old Delhi, bringing the dishes of the royal kitchen to the streets and consequentially giving birth to the famous Matia Mahal food street of Jama Masjid. At the heart of this lies Delhi’s beloved Mughal cuisine outlet, one that remains of choice even today, Karim’s.

A paradise for non-veg lovers, Mughal cuisine runs deep through the walls and stairs of Karim’s, with extravaganzas from Mutton Korma to Fish Tikka Biriyani. Situated within a humble atmosphere, the restaurant poses no frills, with cooks stirring huge stainless-steel pots and grilling kebabs on sizzling skewers. Moreover, Karim’s’ popularity runs throughout the city of Delhi. One might have to wait for hours to get a seat at the restaurant on a Sunday evening!

Three years back, my first visit to Old Delhi all the way from Gurgaon took me to Karim’s where I had the best flavours of Mughlai chicken and naan with my uncle! Not only that, Karim’s presents a humble ambience with people huddled together enjoying their meals within a century-old little shop that is unlike most contemporary restaurants.

– Raghav Rohilla, a student at the University of Delhi.

Visiting Karim’s on a Monday morning presented quite an enthralling experience. Besides the hubbub of Mondays, the restaurant was moderately crowded, with waiters tallying orders and the delicious smell of Seekh Kebabs and Mutton Biriyani wafting through the air. Ordering a plate of the same Mughlai Chicken with Rumali Roti, it took only a few minutes for the plates to arrive. The juicy chicken bathed in spices, wrapped with the paper-thin roti, melts in one’s mouth, presenting a beautiful confluence of spicy, tangy, and divine flavours, as if connecting one to the eighteenth-century Mughal age. But what’s noteworthy here is that, despite being established more than a century ago in 1913, the restaurant preserves the same recipe passed down by the founding chef, Haji Karimuddin.

Nargisi Kofta and Mutton Biriyani are a must-try at Karim’s. In Nargisi Kofta, Mutton Keema is coated on the outside of a whole egg and both are then fried and put in a curry and it is a mouth-watering dish! Coupled with Kheer and Sharbat-e-Mohabbat makes it the most wholesome meal one can ever have!”

– Shayan Basu Roy, another DU Student.

Not to be confused with the popularised food chain Kareem’s, the Karim’s of Jama Masjid prides itself upon its legacy of preserving the ancient recipes straight from the Mughal kitchens, while Kareem’s is a Mughal eatery belonging to the Mumbai-based businessman Kareem Dhanani, established much later than the legacy shop. However, trademark disputes have arisen between the two since 2022, with the intervention of the Delhi High Court. But let’s not loiter and come back to the delicious food, which forms the subject of discussion here.

Located in a little corner of Old Delhi, the restaurant draws people from all around the city and beyond. There is something special about Karim’s besides its heavenly flavours of food and its ‘Purani-Dilli’ glamour and charm.

I once visited Karim’s during Eid and it was really crowded but so lively. In Muslim households, you usually have this concept of Wazwaan, with one big plate of food and everybody eating together out of it. I think Karim’s also reflects this similar concept where complete strangers may be seated opposite to you on the same table enjoying their individual plate of food but you can always reach out and start a casual, friendly conversation with them. This makes for a very harmonic atmosphere.”

– Adds Shayan to his experience with the charm of Karim’s.

Worshipped for its divine delicacies, its homely ambience, and its vintage charm, Karim’s serves as a magnet for all, irrespective of whether you are a foodie or not. A visit to Purani Dilli is incomplete without a pilgrimage to Karim’s, embracing the feeling of being gradually transported to the royal Mughal era, savouring the tastes that some royal princes did too, sitting on the same steps of this little humble shop, nearly hundreds of years ago!

Read Also: Ten Food Joints that DU Freshers Must Visit

Featured Image Credits: Youth Ki Awaaz (Google Images)

Priyanka Mukherjee

[email protected]