Recently, headlines of the NIRF ranking started circulating in print and social media, sparking a discussion over the credibility of this ranking framework. Some of the most well-known allegations levelled against the legitimacy of this evaluating mechanism include data manipulation, corruption, and a lack of transparency. But are concerns like data manipulation and transparency the sole reasons, or are there flaws in the ranking framework’s entire methodology?

National Institutional Ranking Framework(NIRF) is a national-level government institution ranking system that was approved by the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) and launched on 29th September 2015. This ranking outlines a methodology drawn from overall recommendations and a broad understanding arrived at by a core committee set up by MHRD. For the last 7 years, Miranda House has been ranked as the best college in India. Almost every year, at least 5 colleges of the University of Delhi appear in the top 10 of the NIRF ranking.

The most heated discussion in student groups on the credibility of the NIRF ranking starts when a south campus college emerges in the top 10. With little focus on the ceilings of their college rooms, which frequently visit the classroom floor, which helped the college obtain 10th position last year and 9th this year.

-A student of Kirori Mal College

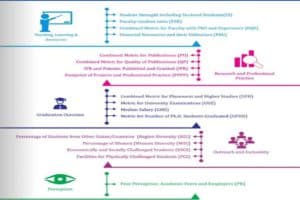

The NIRF ranking primarily ranks institutions based on five major parameters. Each parameter shares a separate weightage. The most alarming aspect of these metrics is that academic achievement of a college is given 80% weightage, which includes Teaching, Learning & Resources, Research & Professional practice, and Graduation outcome, while Inclusivity and Public Perception are given 10% weightage, each. When you look closely at the sub-parameters of each parameter, you will notice that the majority of the criteria that should be regarded as crucial for any public institute are either absent or there for the sake of being included there.

Investment in education has declined significantly in recent years. This reduces the budget that a college is granted each year, forcing institutions to seek alternative funding sources. Utilization of even granted funds is challenging for a government institute, forcing educational institutions to raise funding from private corporations to continue providing students with basic amenities and to preserve their reputation and status. So, if you look very carefully at everything, you will see a close connection between every little thing. NIRF is nothing more than a key to the systematic privatization of public institutions.

-Rudrashish Chakraborty, Associate Professor, Department of English, Kirori Mal College

In terms of data fabrication, one subparameter of Teaching, Learning, and Resources (TLR) is one of the most disputed. The student strength subparameter in the year 2022 ranking is what drew attention to this problem.

Amid the admission of the fresh batch after the cancellation of class 12th boards in 2021, headlines and reports of over-admission in DU began to circulate. Hindu College was one of the most hit, with 146 students admitted to B.A. (H) Political Science, a subject with a sanctioned capacity of 49 seats. Even with such a large admission intake, Hindu College maintained the same score in the student strength metric, which is computed based on the number of students accepted to the sanctioned allowed intake. Similar trends can be observed in SRCC, Miranda House, IP College, and many other DU colleges.

| (Score out of 20) | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 |

| Miranda House | 18 | 18 | 16 | 16 |

| SRCC | 14 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Hindu College | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| IP | 14.53 | 14.60 | 12.59 | 12.73 |

Many argued that the score stayed constant since there was little variation in overall strength. However, it is more concerning that the score was balanced by over-admissions in a few courses and under-admissions in others. Such cases concern the quality of education of such institutions. Not just over-admission, but also under-admission, has an impact on the quality and choice of subjects, particularly for Honors degree students, who are obliged to study what is given or subjects towards the bottom of their preference triangle, as their options for DSE decline with low student strength.

Almost all DU institutions are equally inundated, yet the finger is pointed at the legitimacy of the ranking when a south campus college enters the top 10.

I remember opening my class’s unofficial group, which was flooded with 120+ messages. My classmates were discussing how ARSD could be in the top ten when north campus colleges like SRCC and Stephan’s are ranked 11 and 14, respectively. They don’t care about their institution’s rating, which isn’t even in the top 50, but they doubt the ranking of another college just because it isn’t on the north campus?

-A student of Ramjas College

The divide between the North and South campuses of Delhi University (DU) is largely rooted in the University’s historical development and the initial establishment of its colleges. North campus, being one of DU’s oldest, has an extended history and is home to some of the most prominent and known colleges. This historical advantage has contributed to the idea that North campus institutions perform better or have a higher standing than South campus colleges.

The presence of notable alumni from North campus universities such as Amitabh Bachchan, Shah Rukh Khan, Naveen Patnaik, Manoj Bajpayee, Nimrat Kaur, Amitav Ghosh, and many more build up the belief that these colleges are more prominent. These graduates have achieved significant success in a variety of disciplines, including acting, politics, and writing, adding to the North campus institutions’ history and reputation. The establishment of DU’s South campus, on the other hand, is relatively newer than that of the North campus. South campus colleges emerged and developed in response to Delhi’s expanding demand for higher education and the necessity for new academic institutions. As a result, the South campus lacks the long-established history and the same roster of famous alumni that the North campus possesses”

-Piyush Tiwari, Shaheed Bhagat Singh College(Morning)

To some extent, the idea that South campus colleges are questioned or seen as inferior is probably related to this lack of historical significance and a smaller number of noteworthy alumni. It is crucial to highlight, however, that this notion does not always represent the quality of education or the potential for success of students attending South campus universities. Academic standards, staff expertise, and learning and growth opportunities might differ amongst institutions on both the North and South campuses. ARSD has one of the top science faculties at DU, as well as better infrastructure than north campus colleges such as Kirori Mal, Hansraj, and Ramjas.

“It is ironic that institutions are obsessing so anxiously about their ranks when they themselves advise students not to worry about marks and the rat(e) race and focus instead on learning”

-Prof Anurag Mehra, Head of Department of Chemical Engineering, IIT Bombay in an article in NDTV

Prof Mehra in his article, “The Far From Magnificent Obsession with Ranks at IITs,” mainly addresses the ranking structure in the context of IITs, but he also critiques the methodology’s two fundamental parameters, “Research and Professional Practice” and “Graduation Outcome.” Professor Mehra writes:

“Having more teachers does not necessarily mean that teaching is better, or that the teachers are good. Having a larger fraction of students graduating does not imply that their degree is truly worth something. It can also imply that the university has set very low standards to pass students. Publishing more papers does not tell us much about the quality of research. In fact, the correlation can sometimes be inverse. Too many publications may suggest a lot of incremental work, while fewer papers may signal that these have something significant to say. A very impactful paper will have many citations but a large number of citations does not imply that a paper is great. This is because research communities have a spread across quality and we often have a situation where a large amount of mediocre, incremental research simply cites similar research. In metrics-based calculations, an institution that publishes a large number of low-quality papers will almost always win against one that publishes a few high-quality papers.

The focus of NIRF parameters on quantity rather than quality is one of the most alarming shortcomings and the strongest point that strengthens the foundation of questioning the legitimacy of this ranking framework system.

The vast majority of articles criticizing the reliability of NIRF focus on these three metrics, with some also focussing on the “Peer Perception” criterion. There is little to no discussion of NIRF’s worst-framed parameter, “Outreach and Inclusivity.” One of the reasons that even critics of this ranking fail to address the Outreach and Inclusivity parameter is a lack of awareness in their age group. The most vocal critics of NIRF are senior professors who have little to no knowledge of queer issues, women’s issues, or racism experienced by northeast and south students. The same is true for those who developed the ranking system.

The issue is that people who design these parameters are individuals who have been conditioned to sound inclusive.

-Rudrashish Chakraborty, Associate Professor, Department of English, Kirori Mal College

The Outreach and Inclusivity parameter, which receives only 10% of the weightage, is divided into four sub-parameters: the percentage of students from other states/countries, the percentage of women, the percentage of economically and socially challenged students, and facilities for Physically Challenged Students.

It is evident that a women’s colleges will receive full marks in the percentage of women subparameter even if the institution fails to offer a secure environment for them, even in an all women’s college. Whether it’s the Diwali Mela last year in Miranda or the Reveri Fest night in Gargi in 2020. Even after many complaints and CCTV recordings, they still fail to provide justice to the women of these colleges.

-A student of Gargi College

The fact that there are no parameters or subparameters related to campus safety and sexual harassment laws reflects the government’s and institutions’ incompetence. Even after multiple instances of men scaling the walls of DU colleges, the administration has consistently failed to provide justice and safety, and if students at India’s top colleges are not safe from such harassment from both outsiders and college administration, one can only speculate what students at the lowest-ranked colleges can expect.

The fight for DU’s queer students is far away from over. There are queer collectives at a lot of DU’s colleges, but all except one are unofficial and are not recognized by the college. Homophobia and transphobia are quite frequent on campus, and the college administration’s failure to address the issue leaves queer students with little choice but to seek refuge in these spaces for their safety. Miranda House is the only college in Delhi University with an official Queer Collective.

I’d say Miranda House’s QC is one of the most inactive in the entire DU circuit. Other colleges’ unofficial QCs are more active. It seems that involving the administration makes it harder to get stuff done. However, during the NAAC visit, it is depicted in such a way that the administration is doing all possible to help this community through this society.

-A student of Miranda House

Not only that, but the DU college administration exploits this one sub-parameter as a subject to get marks without having to study. Even though the colleges fail to provide basic amenities, the majority of DU’s colleges in the top 50 have a score of 20 out of 20 in facilities for Physically Challenged Students.

Our college’s science block does not have a lift and a ramp to access the science block from the main block. Just days before the NAAC visit, the Centre for Disability, Research, and Training was allotted a room, which can be found at the other end of the college near the hostel. Most PwD students find it challenging to gain access to that room on their own.

-Aarish Gazi, Kirori Mal College

One of the most shocking revelations can be seen in the Economic and Socially Backward Students category, which is calculated on the number of UG students who receive a complete tuition fee waiver. Most DU colleges have a score of less than 3 out of 20, and their scores have fallen after the implementation of CUET. This raises questions about the diversity of students from various economic and social backgrounds at public universities such as DU.

One of the most difficult issues in ranking systems is the addition of subjective criteria such as “perception” or reputation, which is also a NIRF ranking parameter. While it attempts to include qualitative factors, perception may also be impacted or controlled. Institutions might intentionally choose survey participants or engage in other practices to artificially boost their reputation. This might lead to a distorted perception that does not correspond to the institution’s true quality or originality.

The most important question that arises is: Who is the target audience of these frameworks? Is the government listening to them in coming up with solutions that can bring most (if not all) higher education institutions on the same page? Undoubtedly, it is a matter of celebration for the institutions leading the ranks, but the precarity of the scenario that this NIRF presents also needs immediate consideration and effective action.

-Kaibalyapati Mishra, Junior Research Fellow, Centre for Economic Studies & Policy, Institute for Social & Economic Change, Bangalore, and Krishna Raj, professor of economics, Centre for Economic Studies & Policy, Institute for Social & Economic Change, Bangalore in an article in DownToEarth

In conclusion, rankings often focus on the overall institutional level, which may not represent variations in performance between individual departments, programs, or disciplines within an institution. University systems are complicated, with several departments and programs, each with its own set of strengths and areas of specialization. These accomplishments may be underrepresented in the overall institutional ranking. Institutional rankings frequently prioritize quantitative measures such as research output, faculty-to-student ratios, or funding, which can create an environment that encourages institutions to prioritize these metrics over broader educational goals such as fostering critical thinking, creativity, and personal development. This discrepancy can result in a gap between the ideals that institutions proclaim and the measures that they prioritize.

However, it is worth noting that rankings might be useful in offering an overall assessment of institutional quality and repute. They can help prospective students, researchers, and employers collect preliminary information and make well-informed judgments. Rankings may also serve as a benchmark for colleges to evaluate their performance and identify areas for improvement. Along with their pursuit of rankings, colleges should prioritize a student-centered approach that supports genuine learning, personal growth, and the development of critical skills. By doing so, they could deliver a more balanced and meaningful educational experience for their students.

Read Also: NIRF Ranking 2019: Delhi’s Miranda House and Hindu College ranked as Top Colleges

Featured Image Credits: Devansh Arya for DU Beat

Dhruv Bhati