The National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam has been released, bringing about landmark changes in the citizenship picture in the state. Some Assamese students at the University of Delhi (DU) tell their tales.

About four years after the exercise first began, the NRC list was finally completed and released on 31 August. Monitored by the Supreme Court, the NRC was a massive headcount exercise that sought to differentiate legitimate Indian citizens from “illegal” or “undocumented” immigrants who migrated from other countries – especially Bangladesh – into the state of Assam.

Out of the nearly 3.3 crore people who had applied for inclusion in the NRC, around 19 lakhs have been excluded from the final list. Contrary to speculation, the people who have been excluded would not be considered foreigners or deported; they have a 120-day window to appeal to the quasi-judicial Foreigners Tribunal to have their claims considered. If unsatisfied with the decision of these tribunals, those excluded also have the option of appealing to the higher courts.

A student of DU, who hails from Assam, said, on conditions of anonymity, that the whole NRC exercise had been undertaken to reap “political benefits”. He highlighted how the NRC was received in Assam: “We saw it in a mixed-light; it was good in the sense that the demography of Assam had changed because of illegal immigration, but we also had doubts…When the Assam Accord was signed in 1985, the deadline [for determining Indian citizenship] was set at 1971. So, there was a 14-year gap between the deadline and the signing of the Accord. If the NRC was implemented during that time, then maybe things would have been different; now, nearly 35 years have passed since 198/. If an illegal immigrant did actually come [to India] in 1972, after the cut-off date of 1971, then they would have had children and grandchildren by now. So, there would be two generations of people who would have been born in India, but now would get disenfranchised as Indian citizens, so it would create a humanitarian problem.”

The student also said that the Bangladeshi Government would never accept the illegal immigrants back to their country as they had always been “unaccepting of the fact that illegal immigration has taken place from their land.” The whole exercising had the potential of deepening the divides in the state, he said.

Even though our source claimed that he and his family had all the requisite documents for proving their citizenship as they were all born and brought up in Assam – while their forefathers had come to the state around the time of partition – he said that they still had to face troubles. “Our citizenship status was declared as descendants of foreigners when there is nothing of that sort because we have all the requisite documents from 1954-55. “My grandfathers migrated long back, did their job here, resided here, they had their names on the voter list,” he told us. A serious hindrance was lack of access to information: “Nobody was able to answer our questions as to why our status was like that. Just because we didn’t have access to high ranking officials. So, you don’t have any access to information, no checks and balance mechanism about why your status was like that,” we were told.

Even government officials involved in the exercise admit to the practical hardships. Another Assamese student, a family member of whom is an official involved in the process, recalled a conversation when the latter told her about the practical difficulties being faced by the people: poor and illiterate people suffered the most, while the recent floods had also made matters worse.

The first student continues his story: “Even though the idea of NRC is good, throwing people out is not a pragmatic option. Just telling someone that even though you and your father were born and brought up in India, you are not an Indian citizen because your grandfather or great-grandfather was an illegal immigrant is not something which, in a democratic country like India, we are accustomed to or would want to do.” Neither was throwing people out a pragmatic option, nor was keeping them in “concentration camps” right for a democratic country to do, he said. “It would not be any different from China keeping Uighur Muslims in camps.”

So what could be done? “Maybe designate them as D-voters [Doubtful Voters] and not give them some residential, property or voting rights that normal Indian citizens get,” our source said. But, as would seem evident, he was quick to point out problems with this too. “This cannot help change the demography of Assam because if people can’t be thrown out then whoever resides today at this point of time will always be there. So it doesn’t address the main concern of the Assamese people about their demography being changed. The ultimate purpose of this exercise goes in vain, according to me.”

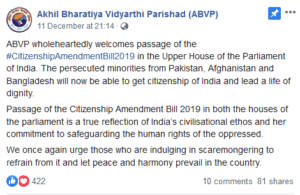

The NRC was not the only recent citizenship-related controversy that rocked the north-eastern states. The Citizenship Amendment Bill of 2016, or CAB, was a piece of legislation which also created a widespread row in the North-Eastern states – and it was not limited to just Assam. The Bill aimed to provide citizenship to people belonging to minority faiths in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan – Hindus, Christians, Sikhs, Paris, Buddhists, and Jains – who were forced to flee their home countries owing to religious persecution. It also reduced the time period of continuous stay in India needed to become an Indian citizen by the process of naturalisation from a period of 11 to six years. The Bill saw massive protests in the north-eastern states. Some of the ruling BJP’s own allies from that part of the country broke away from their political alliances. The Bill was passed in the Lok Sabha but lapsed in the Rajya Sabha.

Our source tells us that Assam was divided in their support for the CAB. The Brahmaputra Valley, with a predominantly Assamese population, opposed the Bill, while people in the Barak Valley – largely Bengalis – supported it. Manas Pratim Sharma, a student of Hindu College, also pointed out this dichotomy in an article he wrote for the North-East magazine of the college. The first student continues by saying that he has had to explain to a lot of people his reasons for supporting the CAB. “The CAB does not say that new people would be brought in from Bangladesh, Pakistan, etc. into India. It talks about whoever has come on or before 31st December 2014; it talks about those who are already here and they will be provided Indian citizenship by process of naturalisation over a period of six years. I don’t think the people residing in north-east or any part of India can be kicked out or be held in concentration camps. Then the CAB makes sense as it addresses people from religious minorities in neighbouring countries who have fled because of political and religious persecution,” he said.

However, taking cognisance of the huge protests that erupted over the CAB, the student also said, “If there is a huge uproar in the NE, then I’d actually be okay – I’d want it, in fact – if people who have migrated on or before 2014 and have not yet settled down in the north-eastern states be shifted to some other parts of the country and be rehabilitated there. This would not be the first time this would happen; it has happened in 1947, 1971, 1984 and other times also. I think there is scope for the government [to do this] so that the north-eastern states don’t have to bear the brunt of migration that the Indian state faces and that it’s evenly distributed, because that is also a primary concern of the north-eastern people…One part of the country should not disproportionately take the burden [of immigration]. If that condition is met with, I’m fine with the CAB in light of the NRC.”

A noted disappointment over the disproportionate share of migrant intake as experienced by the north-eastern states was also seen in Mr Sharma’s article, where he says the following in light of the CAB: “There is a perception that the passage of the CAB will open the floodgates for a fresh wave of influx of Bangladeshi Hindus to India, and Northeast will have to bear the brunt of the next wave of influx again.”

The students we spoke to were secure. Their names were there in the final list, even though some had not appeared in the earlier drafts, despite the names of their families being mentioned. As things stand, 19 lakh people have been excluded. As many media reports showed, there were numerous discrepancies in the earlier drafts: not everyone from the same family was included; relatives of government officials and servicemen were excluded and so on. It is likely that most of the excluded people would appeal to the Foreigners’ Tribunals. Illegal immigration is a real problem for any country; even more so in states of the north-east with a sensitive indigenous cultural demography. It can be hoped that the State would carry out the subsequent phases of the exercise with precision while keeping humanitarian concerns in mind.

Feature Image credits – India Today

Prateek Pankaj

[email protected]