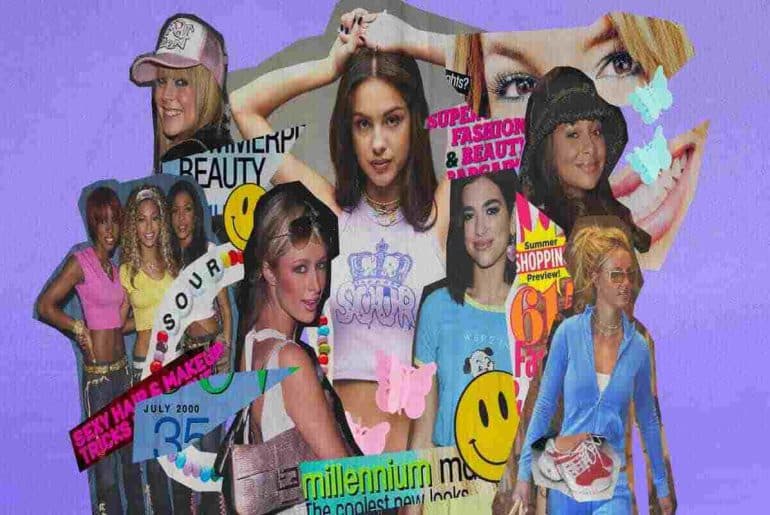

The 2000s have been back for more than two years now, and so have their impossible standards for thinness. But this time around, many are pushing back against the idea that some styles are just not meant to be worn by anyone without the body of a runway model.

The 2000s were known for the emergence of fashion trends that bared either your abs or your insecurities, from low-rise everything to skin-tight outfits. Baby tees, tube tops and low-waisted jeans with underwear peeking above them were only a few of the audacious styles that were popular during the decade.

They were also known for their rampant fatphobia and glorification of nearly unachievable bodies. Exemplified by socialities like Paris Hilton and Victoria’s Secret Angels, this body was long, lean, busty and, most importantly, perfectly toned.

Every other kind of body was deemed unattractive and relentlessly shamed, something that is all too apparent when we look back at the pop culture of the era.

Kim Kardashian’s now-idolised figure was referred to as a disgusting result of her bingeing on junk food, especially in comparison to her friend Paris. On iconic TV shows like FRIENDS and Sex and the City, a character’s (past or present) fatness was often the punchline.

Even the women who did fit into these narrow standards were not spared. Lindsay Lohan, Kristen Stewart and other actresses had every pound of weight gain scrutinized and documented by the paparazzi. When they lost too much weight or, like Kiera Knightley, were simply too skinny in the first place, they were accused of having eating disorders and being desperate for attention.

Of course, the 2010s that came after weren’t exactly a utopia where all bodies were accepted as they were. After all, Brazilian butt lifts, the world’s most dangerous cosmetic procedure, Facetune and waist trainers rose to popularity in this decade. And thinness was still seen as desirable, even if it wasn’t a necessity for being considered attractive as it had been in the ‘90s and ‘00s,

Still, with the rise of the body positivity movement, a far wider variety of bodies were seen as acceptable or even appreciable than at any other time in recent history. Celebrities were still shamed for weight gain or loss, but it was usually the trashiest tabloids doing it, not Cosmopolitan magazine.

The fashion trends of the 2010s like athleisure, high-waisted bottoms and flowy midi skirts were also far more forgiving of most of our physical “imperfections” than the previous decade’s fashions.

But fashion, like most other forms of art, is said to follow the ‘20-year rule’ where trends die out and come back in style within about 20 years. So, it was inevitable that with the beginning of the 2020s, early 00s trends like baguette bags, claw clips and, of course, all of those clothes that laid out all our insecurities for public display would come back in full force.

Also inevitable was the return of the hunger for the 2000s body.

Kim Kardashian and Doja Cat have been rumoured to photoshop their curves smaller and get their body implants taken out. Thin celebrities are doing the exact opposite—showing off their naturally lean frames in Y2K styles instead of camouflaging them with hip pads(!) and clever angles.

And it isn’t just the professionally beautiful who’ve begun to crave model-like thinness once again. “How to get 2000s skinny” is a popular Google search and Pinterest boards called variations of “outfits for when I’m skinny” are popping up with increasing frequency. “Pro-ana” content that glorifies anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders that originally emerged on Tumblr and internet forums in the late ‘00s is making its way back to social media, particularly TikTok.

But not everything’s stayed the same. Many women, including popular plus-size fashion influencers, are embracing bold, beautiful Y2K styles but rejecting the baggage they originally carried.

Instagram models like hollymarston, v.zozimo and francescaperks play around with 2000s-inspired outfits that range from sexy and fierce to playful and sweet.

The popular “Is It An Outfit Or Is She Just Skinny?” trend on YouTube also reveals increasing awareness about the role a thin, fit body plays as the most important accessory in many outfits. In these videos, women try on outfits that were praised as incredibly fashionable on skinny celebrities and models, often confronting insecurity about their own perceived imperfections, and decide if they really are stylish or if it was just the wearer’s aspirational body that made them seem that way.

But that certainly doesn’t mean that Y2K fashion, or trendy clothing in general, is accessible to everyone. The vast majority of these clothes are only available in a very limited range of sizes. They are often also not designed to fit curvaceous bodies, whether they plus-sized or not.

The women who’re regarded as the trailblazers of this trend, from Bella Hadid to Megan Fox to Charli D’Amelio, fit perfectly into the 2000s mould. It’s unsurprising that most of us who don’t look like them fear judgement and disdain if we try to replicate their looks, even if it wouldn’t be expressed as openly as it was 20 years ago.

But things are changing, and that remains a cause for hope. We may not all have the confidence or desire to wear cut-out bodysuits and thong-baring pants, but most of us can agree that a woman who does can, even if she’s not a size XS.

You can pry my high-waisted skinny jeans away from my cold, dead hands, though.

Featured Image Credits: NBC News

Read also: Auburn Umbrella – Iconic Cinema-Inspired Fashion Trends

Shriya Ganguly [email protected]