Ed-tech startups like Byju’s and Udemy promised to revolutionise the Indian education system. Instead, they’ve turned it into a ruthless and exploitative money-making machine.

The COVID 19 pandemic came as one of the greatest blows to education in modern history. It shut down schools, left millions of students stranded and forced them into child labour and marriage. But for one industry, educational technology the closing of classroom doors was exactly what cleared their path towards monumental success.

Byju’s, the most successful of these ed-tech startups, has been valued at USD 18 billion, more than the entire education budget of India for 2021-22. It has acquired other education brands like JEE and NEET coaching giant Aakash Institute, WhiteHat Jr., a company that claims to teach kids as young as 6 to code and skill-development app Great Learning. It has even gone international, buying up Epic!, Osmo and other American education companies.

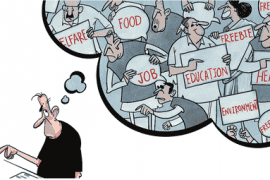

Fueling its meteoric growth are huge investors like Edelweiss and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative as well as a host of unethical practices that swindle students and parents out of their money by making misleading claims and false promises. And Byju’s is certainly not unique, most other ed-tech platforms have adopted similar strategies for profit.

Byju’s incessant flashy ads starring Shah Rukh Khan and WhiteHat Jr.’s promises to turn kids into computer geniuses who create apps worth billions at age 12 might be egregiously false and very irritating, but they’re far from their most outrageous techniques for selling their services.

Toxic Work Cultures

Byju’s employees are reportedly made to work more than 12 hours a day, skipping meals and rushing from one potential client to another in order to meet their weekly target of INR 2,00,00 per week. They target everyone from 6th-graders who say they want to become doctors to 12th-graders struggling with competitive exams (and, of course, their parents) and convince them that they will never be able to succeed without Byju’s or one of the companies it owns.

To do this, they partner with schools to push their courses among students, prey on parents’ insecurities by asking their children questions that are too advanced for them and convince parents in smaller towns that local coaching institutes will be utterly inadequate in preparing their children for national-level exams.

Even student interns hired by the company aren’t spared. They are asked to push the service onto their peers and convince them to first sign up for a free trial and then buy the courses. They often receive calls from frustrated and angry parents who are tired of Byju’s insistent marketing.

Students were not ready to take up the free lectures as well because later on they used to jam up their parents every now and then to take up the course.

Disha, a former intern at WhiteHat Jr.

Targeting the Most Vulnerable

Until relatively recently, Byju’s reach was limited to the digitally-literate elite. But after they launched Discovery School Super League, an inter-school game show, they saw a sharp increase in sign-ups from students of less-privileged backgrounds. So, they decided to fully capitalise on their new market.

Employees were asked to sell the course to everyone in their lives, from the owner of a chai stall they frequented to their domestic workers. The company also collects data from their phones that have downloaded the Byju’s app that allow them to guess the owner’s socioeconomic status and tailor their marketing strategies to it.

When speaking to poorer families, sales associates make their children seem incompetent and tell the parents that their only path to academic and professional success is through a Byju’s education. To enable them to pay for these courses, which can cost lakhs, they encourage them to take up loans. To facilitate this, they even have tie-ups with companies that offer these loans but take care never to refer to them as “loans” or mention “outstanding payments” to make sure potential clients aren’t driven away by the idea of borrowing money. Unsurprisingly, a survey by The Ken found that more than half of the people who were signing up for these subscriptions had no idea that they were taking a loan.

My driver was scammed by Byju’s. They sold him a course of 35,000 for his daughter and convinced him to take a loan for it by telling him all sorts of misleading things. His daughter kept insisting that it was very important and he thought it best to listen to them because he was not highly educated himself and was uninformed about these things. Now he has to borrow money from me and struggles to pay instalments every month.

Anya, a second-year student of DU

Unhappy Students

Byju’s promises to refund clients who are unsatisfied with the service and cancel their subscription within 15 days of purchasing it but many parents claim that this is a false promise. Many of them who have been denied their money have taken to social media platforms like Twitter and LinkedIn to publicly voice their grievances. Often, the threat of public disgrace has turned out to be the only way to make the billion-dollar company pay up. Once again, those who do not have the privileged knowledge or ability to access these platforms are left in the lurch.

The quality of the teaching and learning resources themselves on ed-tech platforms is highly inconsistent. Some have found the classes useful but have been frustrated by repeated attempts to convince them to buy even more Byju’s services. Others say that they did not even receive most of the services they were promised, let alone find them satisfactory.

“Overall the e-learning part was helpful… although they would keep on calling you until you enrol in the physical classes. But the physical classes turned out to be a pain for me.” – Devyanshi, a first year student of DU whose school partnered with Byju’s

My younger brother signed up for a 3-month course with Byju’s which was supposed to come with personalized guidance. The learning material itself was decent, but his supposed mentor stopped calling us or replying to our attempts to contact him just 2 weeks after the classes began.

Shreya, a first year student of DU

Worst of all, these companies have been ruthless about suppressing criticism against them in order to maintain their public image.

In 2020, software engineer Pradeep Poonia was sued for a whopping 20 crore by Whitehat Jr. on charges of defamation and copyright infringement. Poonia had uploaded a series of videos criticizing the ed-tech giant and its practices, particularly its ad campaigns, one of which claimed a 9-year-old named Wolf Gupta had got a 150-crore job at Google at the age of nine after learning to code from Whitehat Jr. Along with the lawsuit, Poonia had his videos taken down and social media accounts disabled. Although Whitehat later backed down and withdrew their charges, the extent of their power and influence had been made apparent. Now, anyone who isn’t a multi-billion-dollar corporation knows that going up against these giants could prove fatal.

The Way Forward

Many educators have suggested that the government must crack down on these ed-tech companies and regulate their operations as strictly as they do schools. For instance, their subscriptions must all be turned into monthly ones similar to those of Netflix and Spotify, forcing them to keep their clients continuously satisfied rather than abandoning them the moment the deal is closed.

Others say that the commodification of online education by corporations is a problem in itself. They claim that all the resources available on these websites can be found elsewhere on the internet, from YouTube to the free, non-profit ed-tech organization Khan Academy’s website.

Either way, the pandemic has made online learning an essential part of most students’ lives. If we want to stop it from becoming the monopoly of a few greedy and unscrupulous businesses, we must act now.

Read Also: In Conversation with WeConvert: A start up to change the waste management system in India

Shriya Ganguly [email protected]

Comments are closed.