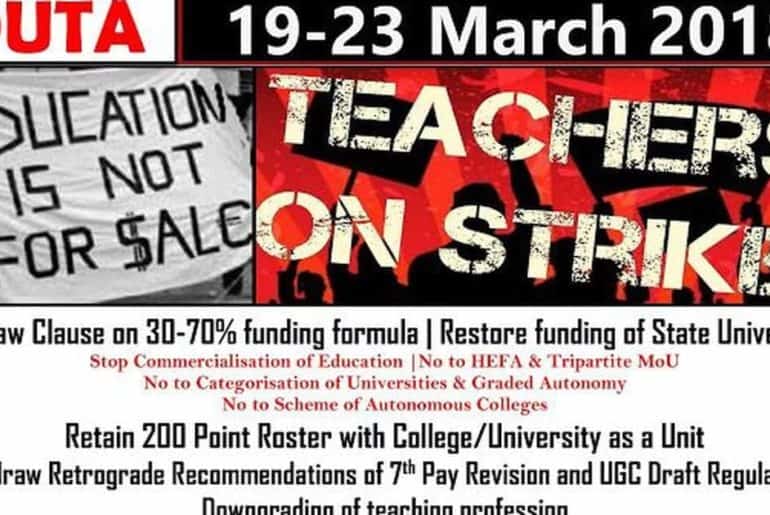

The recent autonomy granted to 60 higher education institutions by the University Grants Commission (UGC) has unleashed debates regarding the increasing commercialisation of the education sector of the country. The Delhi University Teachers’ Association (DUTA) has been on strike for the past five days protesting against the 70:30 ratio of funding recommended for central universities, which would lead to the blurring of line that separates the fee structures of private and public-funded education. Under this new funding formula, universities are being asked to generate 30% of the additional costs towards revised salaries for teachers and non-teaching staff on account of the 7th Pay Revision. If this formula is implemented, higher education will become inaccessible to thousands. The teachers have reportedly called their students to join the strike and show their solidarity. In such a highly charged atmosphere, it is apparent is that our access to affordable, high-quality education is in grave danger.

Ideally, it is the government’s responsibility to invest in higher education (as is the case in countries like Germany, Mexico, Finland), but the UGC’s new funding policy of grants being replaced by loans through the Higher Education Funding Agency (HEFA) for any infrastructural needs of universities means that the burden of providing affordable education would shift to parents and students. This has far-reaching consequences as it would lead to the marginalisation of students from backward communities and sections, an exclusivist academia, and eventually, the homogenisation and unilateralism of critical thinking.

Commenting on similar privatisation of American universities, Noam Chomsky, an American linguist and political activist pointed out how when corporate values and money start to govern the education sector, there are disastrous consequences ranging from greater job insecurity to a division of the society into the “plutonomy” (the small group which has the highest concentration of wealth) and “precariat” (the rest of population who live a precarious existence). Such a thrust for creating profit and hence, an emphasis on vocational courses and skills that would fit a globalised, capitalised world would mean that education would become education for the sake of it, and thereby lose its value. Colleges and universities would be forced to sell their brand, their reputations to generate funds for their use.

The rich cultural diversity of campuses such as DU and the empowerment of marginalised sections through affirmative action would cease to exist. Subjects like liberal arts, minority studies, gender studies, language courses are bound to get sidelined for their sheer ‘impracticality’ in a free-market economy. As Debra Leigh Scott mentions “If you remove the disciplines that are the strongest in their ability to develop higher level intellectual rigour, the result is a more easily manipulated citizenry that is less capable of deep interrogation.” Education would just be another commodity, available to the highest bidder.

What is even more disheartening is the lack of awareness among the students about how much this issue affects us all at the primal level. The fees hike would lead to an exclusive admission procedure, which would in turn increase the social and economic disparity between classes and various regions, leading to greater unemployment and higher dropout rates. The state has been carefully constructing a narrative of “autonomy” that is supposed to give the universities and colleges greater freedom to decide their educational blueprints. In reality, the purpose of education as a social good rather than a profit-making venture, our need for spaces for assertion of our diverse identities and issues, our access to tools for critical thinking and learning— are all getting endangered.

Feature Image Credits: Scroll.in

Sara Sohail

[email protected]

Comments are closed.