Giving rise to a new style of writing – prosetry – free verse has been an essential tool since ages ago, and has been increasingly relevant till date.

Free verse reminds one of the voices of resistance and anecdotes of expression, be it as vocal as it was at the Shaheen Bagh protests or as subtle as ‘Instagram poetry’. It has contributed, ironically, what cannot be measured in verses or penned down in words – an abundance of artistic expression, breaking free from what really ‘art’ is to narrate what can be referred to as ‘prosetry’ of individual as well as the collective self of one’s confrontations with the world. While some have dismissed it as “not worthy” or “not having much to say”, free verse poetry is one of the rawest and most passionate forms of expression.

Types and Styles of Free Verse

Some free verse poems are so short, they might not resemble poems at all. In the early 20th century, a group who called themselves Imagists wrote spare poetry that focused on concrete images. The poets avoided abstract philosophies and obscure symbols. Sometimes they even abandoned punctuation.

The apparition of these faces in the crowd:

Petals on a wet, black bough.

- Ezra Pound’s poetry, Imagist Movement

More reminiscent of a haiku than of Pound’s Anglo-American poetic forebears, this poem packs enormous meaning into a mere fourteen words. In just two lines, Pound describes both a setting and an unspoken mood, as well as a speaker’s perspective.

Other free verse poems succeed at expressing powerful emotions through run-on sentences, hyperbolic language, chanting rhythms, and rambling digressions. Perhaps, the best example is Allen Ginsberg’s 1956 poem “Howl“. Considered to be one of the greatest works of American Literature, the poem consists of 112 paragraph-like lines in more than 2,900 words and can be read as three strikingly lengthy run-on sentences.

Therefore, free verse goes on to compose a story, tell a tale, and weave a narrative – something that Geoff Ward, a renowned writer and poet, refers to as “prostery”. Even though it doesn’t look exactly the same as prose when penned down, when read out loud, it does make more sense as prose, which further tells us that free verse poetry ‘must be heard’.

Am I good enough?

I’m not really sure.

In fact, I’m sure I’m probably not.

What made me think I could write this poem?

Everyone will laugh at it when they read it,

Or worse, they will be silent and hold their criticism in.

Or worse yet, they’ll say exactly what they think and I’ll be crushed.

Or worst of all, they’ll tell me it’s great but not mean it.

And even if they truly love it, I’ll still wonder if it’s good enough

– ‘Endless Self-Doubt’, Kelly Roper

Origin of Free Verse

Tracing its origins can be a daunting task as they appear to be rather ambiguous: the first poets of Ancient Greece composed in lines unstructured by syllables and rhythm at the time lyric poetry was being developed. There are traces of free verse in the Middle English ‘alliterative revival’ (c1350–1500), which was differentiated from Old English verse by its looser structures and many rhythmic variations. Clear instances of the same are ascertained in the translations of The Song of Songs and particularly, King James Version of the Bible (1611) – for instance, Psalm 23, ‘The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want,’ which went on to influence one of America’s most influential poets, Walt Whitman. He contributed more to free verse than anyone else of his contemporaries. In his early 30s, Whitman decided to focus on his poetry and began writing what would become “Leaves of Grass,” a collection of poems using free verse with a cadence based on the Bible.

(Read also: A Brief History of Free Verse)

When ‘Leaves of Grass’ was first published in 1855, his readers didn’t know what to make of Whitman’s unheard-of informality with the reader (‘Listener up there!’– he gestures toward the end of ‘Song of Myself’) and his shockingly raw, revolutionary subject matter… He was criticized for breaking every rule of good form and good taste — of course, this was all intentional on his part.

- Karen Karbiener, a scholar of 19th century American Literature, NYU

Matt Cohen, a professor of English at the University of Texas, notes that part of what made Whitman special was that he broke the rules of poetry, which at the time meant “writing in rhyme and meter, in stanzas with traditional shapes.” Instead, Whitman wrote in “long, unrhymed lines, with a sort of conversational cadence rather than iambic pentameter or some other meter, and played fast and loose with stanzas and other sorts of organization.” Whitman’s innovations went even deeper. He broke the boundaries of poetry that he believed restricted freedom. In a sense, Cohen believes, by choosing free forms, “Whitman built democracy into his very style.”

20th Century Verse

Free Verse went on to become the centre of the Imagist movement in early 20th century America. Looking back from the 1950s, T S Eliot denoted Imagism as the starting point of modern poetry, when more and more poets began taking up free verse.

The new poetic inclination was not without its detractors, however. In the early 1900s, critics riled against the rising popularity of free verse. They called it “chaotic” and “undisciplined”- the mad expression of a decaying society. In 1916, the American scholar and critic John Livingston Lowes (1867–1945) remarked: ‘Free verse may be written as very beautiful prose; prose may be written as very beautiful free verse. Which is which?’ Robert Frost once commented famously that writing free verse was like ‘playing tennis without a net,’ while the poet and physician William Carlos Williams (1883–1963) said: ‘Being an art form, verse cannot be free in the sense of having no limitations or guiding principles.’

On the other hand, proponents of free verse claim that strict adherence to traditional rules suffocate creativity and leads to convoluted and archaic language. A landmark anthology, Some Imagist Poets, 1915, endorsed free verse as a “principle of liberty.” Early followers believed that “the individuality of a poet may often be better expressed in free-verse” and “a new cadence means a new idea.”

Modern Day Verse

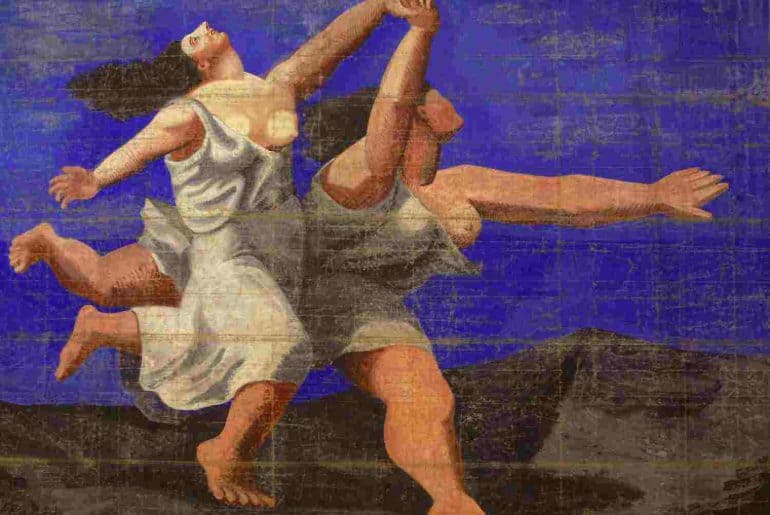

In contemporary times, free verse has evolved to produce some of the best forms of artistic work and expressions, which is a testimony to centuries of altered discourses and changed narratives. Einstein introduced his theory of special relativity. Picasso and other modern artists deconstructed perceptions of the world. Technological freedom and the rise of online platforms has to lead to an abundance of artists, writers, poets, just waiting to be heard. With a newly acquired sense of discontentment from the rat race and the search for meaning in life, while also dissenting against what is considered to be the ‘norm’, poetry has come a long way in terms of personal exploration and experimentation.

Especially with the rise of ‘Instagram poetry’, free verse has broadened, both in existence and understanding. Not unlike before, free verse still implies breaking free from rules and rhymes to express what is necessary – what needs to be written and heard, in a manner free from elitist categorisations or exclusionary meters. The most popular of these ‘Instagram poets’ would be Rupi Kaur, her signature style being short sentences, lower case, free verse, and accompanying illustrations with hidden philosophical implications of self-doubt and self-discovery.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CKpo3JAhL5T/?igshid=1ddpud736y0wn

Even though Kaur’s poetry has been controversial and sometimes criticised for being overly formulaic and monetised, penning it down with the purpose of writing what sells. However, despite the existence of such beliefs and notions, from a personal opinionated space, Kaur’s poems are liberating, to say the least for what or who really defines ‘art’ or if it is ‘worthy’ enough or not. Drawing any conclusions as to what is the ‘acceptable’ form of writing or how to create ‘art’ is up to no one.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CIzAPqzhKa8/?igshid=110l71no1uxsw

Another one of my personal favourites would be Live Wire which publishes poetry submitted by anyone and everyone pertaining to dissent, expression and everything art.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CLzKU36h7ue/?igshid=1r660qphklv2a

It can turn out to be one of the strongest means of dissent and asking the right questions and sometimes, just having a voice to pen down verses of resistance.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CC1iNyqJUIo/?igshid=vg5fhzmazzny

Such poetry also becomes an outlet for altered discourses and deconstructing, and then reconstructing narratives. The purpose, then, is not to create ‘art’ or pen down something to be read by generations to come but just voicing out your epiphanies and ensure your being amid the uncertainty of things.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CLbPN9NBWMI/?igshid=1f4pc5kvpiuij

And sometimes, that’s exactly what they are – ‘prosetry’, narrating beautiful memories and telltales.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CL1_LW5ADIU/?igshid=1f6l2rzppm2xr

What, then, becomes rather interesting is how the continued digressions from its commonly perceived understandings, free-verse poetry today stands for anything and everything devoid of any limitations, accompanied with illustrations, colours and paints, so as to achieve its sole absolute purpose – expression.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CER6rKsACI0/?igshid=py8qbbohb5wr

Therefore, today, poetry dominates the literary scene and only time would tell its lasting impression as wheels on the sand of passing time.

Read also:

https://dubeat.com/2020/03/from-ghalib-to-rupi-kaur-poetry-in-modern-times/

https://dubeat.com/2018/03/slam-poetry-history-culture-and-views/

Featured Image Credits: Unsplash

Annanya Chaturvedi