On December 6, 2024, the Delhi High Court will hear the bail pleas of Umar Khalid, Sharjeel Imam, Khalid Saifi, and Gulfisha Fatima, accused under the UAPA for the 2020 Delhi riots. The continuous rejection of their bail pleas and their prolonged incarceration without trials highlight the precarious state of democratic freedom under India’s current authoritative regime, which thrives off of curbing dissent.

The Unlawful Activities and (Prevention) Act (UAPA), introduced on December 30th, 1967 was introduced as a tool to combat “anti-national” activities. In July 2019, the UAPA Amendment Bill was introduced, which passed due to a heavy NDA majority in the Rajya Sabha. In the words of Home Minister Amit Shah, “Those are terrorists who attempt to plant terrorist literature and terrorist theory in the minds of the young. Guns do not give rise to terrorism, the root of it is the propaganda that is done to spread it.” However, under the pretence of protecting India’s sovereignty and integrity, the UAPA has morphed into the state’s preferred weapon to stifle dissent. It has become a system that suppresses intellect and fights against any knowledge that challenges the government’s authoritarian agenda. GN Saibaba’s imprisonment under the UAPA, which eventually led to his demise, stands as an institutional murder — one of the many cases where the draconian law has been weaponised to quash ideas and voices, with activists like Stan Swamy meeting a similar fate.

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), passed by the Indian government in December 2019, grants citizenship to non-Muslim refugees (Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Jains, Buddhists and Parsis), from the neighbouring countries of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh, provided that they have proof of residing in India for five or more years. It was met with nationwide protests owing to its discriminatory anti-Muslim nature, which was paired with concerns over the proposed National Register of Citizens (NRC). This culminated in the 2020 Delhi riots on 23rd February 2020, killing 53, mostly Muslims. Shortly after, Umar Khalid, Sharjeel Imam, Khalid Saifi, and Gulfisha Fatima were arrested due to their alleged connections to the riots and charged under the UAPA. The UAPA vests authorities with sweeping powers, including arrest and extended detention without trial. It shifts the burden of proof on the accused and strips away the presumption of innocence and also makes the procedure of obtaining bail increasingly difficult.

The evidence presented by the Delhi Police consisted of public speeches, WhatsApp texts and extremely vague witness testimonies – it is as if a student’s passionate speech calling for joint action against injustice was deliberately twisted into a “terrorist conspiracy,” just because they dared to use knowledge and words as their weapons. The absurd reality is that the vision for a Viksit Bharat seems to be one where the state labels students using their knowledge as “terrorists”. The state’s full-blown attack on those who possess knowledge and people’s access to knowledge in the first place is made even more evident in the media coverage centred around the issue.

One news report in a prominent Hindi daily claimed that to leave no stone unturned in inciting the riots, I secretly met Sharjeel Imam in Zakir Nagar, New Delhi on February 16, 2020 – a week before the riots broke out. In reality, on the night of February 16, 2020 – and even the police would attest to this – I was 1136 km away from Delhi, in Amravati, Maharashtra. And Sharjeel Imam on that night – nobody can dispute this either – was in Tihar jail, as he had been arrested about 20 days earlier in a different case. It seemed that the esteemed journalist who conjured all this up did not care to check even the most basic facts.

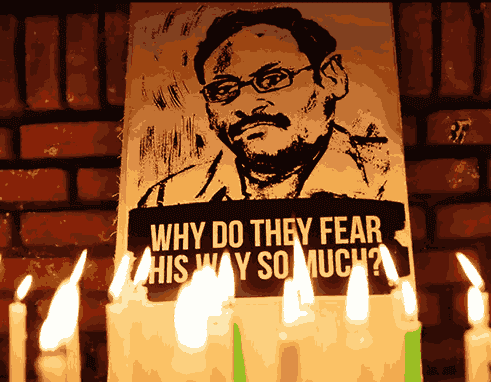

Umar Khalid via the Wire

Umar Khalid, who was arrested in September 2020, is still awaiting a trial. His bail plea, similar to Sharjeel Imam’s, was rejected multiple times, with the court and the Delhi Police consistently highlighting his “significant role in orchestrating the conspiracy to incite violence”. Asif Tanha, a student activist from Jamia Millia Islamia was arrested on similar grounds and was granted bail on June 15, 2021 by a Division Bench comprising Justices Siddharth Mridul and Anup Jairam Bhambani, with both the judges pointing out the differences between protests and terrorist activities. In October 2022, Umar Khalid’s bail petition was however rejected by a Division Bench comprising Justices Mridul and Rajnish Bhatnagar. The varying results indicate a subjective application of justice, influenced not only by the details of the cases but also by the political and social environment surrounding the accused. Khalid’s popularity as both a researcher and a student activist paired with a stronger need to stifle dissent by the authorities may have been possible reasons for his rejected bail plea. Furthermore, the Muslim identity of activists plays a pivotal role in shaping the political narrative, impacting not only legal proceedings but also public perceptions and societal attitudes. This identity becomes a mechanism that delegitimizes dissent and legitimizes severe legal measures in the eyes of the public.

The outcome of the hearing on December 6th will set a crucial precedent in balancing state authority and individual liberties. Dissent is, after all, the act of realising that you have the power to speak. With the Viksit Bharat vision being hyper-fixated on shaping generations of unthinking students, it becomes important, now more than ever, to keep the right to question alive in spaces around us.

Featured Image Credits: BBC / Nehal for DU Beat

Read Also: The Donkey Dance of UAPA: Criminalising Dissent in a Hollowing Democracy

By Sakshi Singh for DU Beat