The displacement of ad-hoc professors has impacted not only the institutions they built but also the bonds formed with their students. Despite being de-institutionalized and separated, these bonds struggle for survival as students refuse to forget. This personalized narrative captures the author’s reflection on the breakdown of the student-teacher relationship post displacement.

When I decided to write this article, I could not gather the strength to collect my thoughts for the longest time. The faculty displacements had impacted me and almost everyone in my department in a way that was both similar to and, at the same time, different from the experience of the entire university. It was a traumatic catastrophe to bear, as it was not merely a politically orchestrated low- blow but also a personal tragedy to us. For many of us outstation students who came from dysfunctional families, were bullied in schools, and were struggling to make friends in college, these young ad-hoc professors, unlike the authoritative school teachers, became our space of solace. They became a safe space in a hostile, daunting, and toxic masculine environment, much like my own college- Ramjas and, to a large extent, the entire university.

The first professor I ever interacted with, in college, from the history department, was displaced from her position within a month of my joining the college. While I was lucky enough to be taught by our department’s professors for over a year, my juniors lost them within a month of their joining, experiencing the cycle of shock, anger, solidarity, and eventually disillusionment. Though the university reduced them to mere numbers and commodities to be replaced, these professors were far more than just numbers and teachers to us. They actively practiced what they believed in and rejected the conservative hierarchy between students and professors. They became like friends to us in college. Not only did their lectures ignite our passion for literature, but they also went the extra mile to support those who were less engaged in the subject. Now that they have been displaced, not only students struggle to maintain their interest in the subject, but many of us, who aspired to pursue a career in academia, find our dreams shattered.

As a literature student, it’s difficult to overlook the issue of praxis, particularly since many new professors have allegedly secured their positions through political connections. Additionally, some associate and permanent professors have disappointed their students across various colleges. They not only failed to support ad-hoc professors but also, as claimed, took advantage of them, contributing to their displacement and the decline of their departments, despite having the ability to intervene. This has created a situation where we feel institutionally separated from the displaced, making it difficult to trust or rely on the newly appointed and associate professors. As a result, the displacements have not only caused socio-economic precarity for the displaced academics but have also profoundly affected the mental health and future career of the students who witnessed the destruction of their departments.

When the notification for permanent appointments was released, I cannot remember a single day without experiencing an emotional breakdown. Despite our hopes and prayers, we knew our professors would not be retained because they stood firm in their moral and pedagogical principles, both in and out of the classroom. They stood firm on the principles the university seemed unwilling to accept.

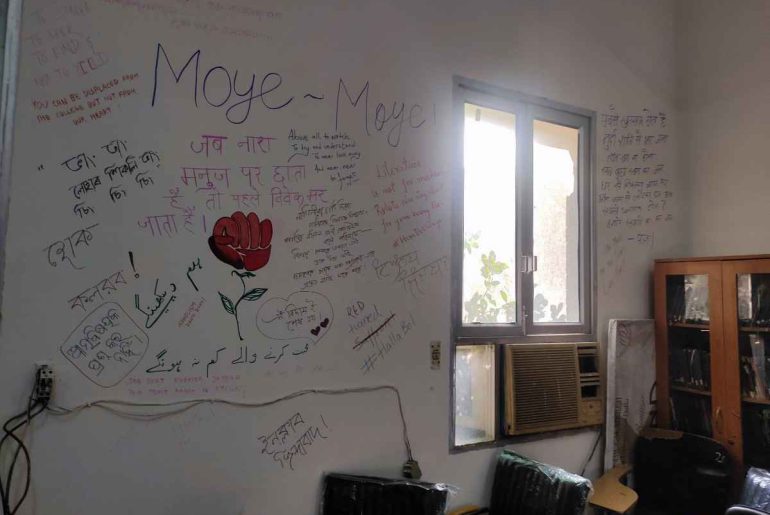

Despite the initial hopelessness of our permanent professors, we students continued to survive, refusing to forget the displacements. This determination manifested in small ways in which we sustained their memories including meeting with them post-displacement as a form of resistance against the separation. I began dedicating my research papers to my displaced professors to address the glaringly huge yet unaddressed threat they faced. I also wrote poems and performed them at various colleges , not only to express my anger but to spark a conversation about this pressing issue. Graffitis and writing messages on the walls of the department and classrooms was another way we sustained the memory post the displacements. While this ensured that a post-memory of the displacements is sustained, solidarity has failed to compensate for the bond we had with these professors.

Although I still interact with them and meet regularly, the displacement has altered the relationship I shared with them, leaving a mutual sense of loss that always remains after meeting them. I often wish our meetings could last longer. Now, if I want to meet them, I have to ‘plan’ a meeting—why has it come to that? Isn’t it unfair to make us long for their presence?Isn’t it unjust for us that we can no longer see them smiling in the corridors, teaching in classrooms, or joking around? Isn’t it unfair that, just as their right to witness our growth has been denied, our right to learn alongside them has also disappeared? I often reflect on a question one of my professors asked after his displacement: “How can they remove us now after so many years of teaching? If we were underqualified, why were we hired in the first place?” I had no answer for him, and neither did the university.

The sheer trauma of being removed from their jobs, decades after their dedicated service, was so profound for some, that they severed all ties with Ramjas—cutting off contact with colleagues and students alike, despite their deep affection for many of them. Even today, there is an unbridgeable distance between us. In a way, none of us has been able to completely move on. More importantly, there remains a huge elephant in the room – their employment. We are still learning how to address it or, more importantly, if at all to address it. We are still coping in our own little ways. 4 December, 2023— I still have a coke bottle, a blackened handkerchief, and a fifty rupee note, given to me by the professors on that day . I have read several texts such as Girish Karnad’s The Fire and The Rain, Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Amruta Patil’s Kari, because ‘they’ taught it. Many of these texts, like them, are institutionally displaced, yet I read them days just before the exams. Though I have stopped taking notes during lectures in my diary, I keep thinking about what ‘they’ would have said about these texts. Despite their displacement, we struggle to remember them, even in the classroom which was once full of their epiphanies.

A newly appointed professor in the college once asked me, “Why were you all so close to your professors? I understand that forming institutional attachment is natural, but it is very hurtful and harmful.” While I agree with them on institutional attachment being hurtful, all attachments hurt, but that doesn’t stop us from loving individuals, right? For many of us, it is partly because of our professors that helped us survive college, rather than our attachment being a cause of harm. Today, it is because of ‘them’ and their pedagogical principles that I can criticize my university’s hypocrisy in offering a paper like ‘’Literature and Human Rights’ after experiencing the tragic loss of Prof. Samarveer Singh.

Despite the hurdles by these displacements, it is certain that nothing can ever break the bond that we share with our professors. These displacements have exposed the seemingly bright yet dreary reality of academia. Today, we continue to take pride in our professors, who may have lost the round in terms of their employment, but have triumphed in the battle of principle. They refused to be a Faustian academic—someone who would compromise their integrity for a job, only to preach morality later.

Read Also: To Meet them Again

Featured Image Credits: Vedant Nagrani

Vedant Nagrani