A lavish new series, Bhansali’s Heeramandi, promises a glimpse into the lives of courtesans in 1940s India. Critics, however, worry that the show prioritises dazzling visuals over historical accuracy. Will Heeramandi offer a fresh perspective on these complex women, or will she simply reinforce stereotypes with her opulent sets and costumes? Does spectacle trump substance, or can Heeramandi educate while entertaining?

The ongoing buzz around Bhansali’s majestic Heeramandi is for its extravagant depiction of the lives of Tawaifs, which comes across as nothing else but an alternative, deranged portrayal of these women’s lives. Bhansali’s work has prioritised aesthetic representation over the realistic narrative of the courtesan culture. Heeramandi: The Diamond Baazar is set against the backdrop of India’s struggle for freedom from British control. The series delves into the lives of Tawaifs within Lahore’s Heera Mandi. The story revolves around a bitter battle for dominance. Longstanding rivals Mallikajaan and Fareedan are caught in a fierce battle to claim the top spot. Mallikajaan seems to have a successor in her young daughter, Alam. But a surprising turn of events arises when Alam defies expectations. She chooses the love of one man over the admiration of many, throwing the future of Heera Mandi into question while also throwing away our expectations in a deep ditch of disappointment with the abrupt absurdity in the plot that follows the sensitised and well-marketed drama series.

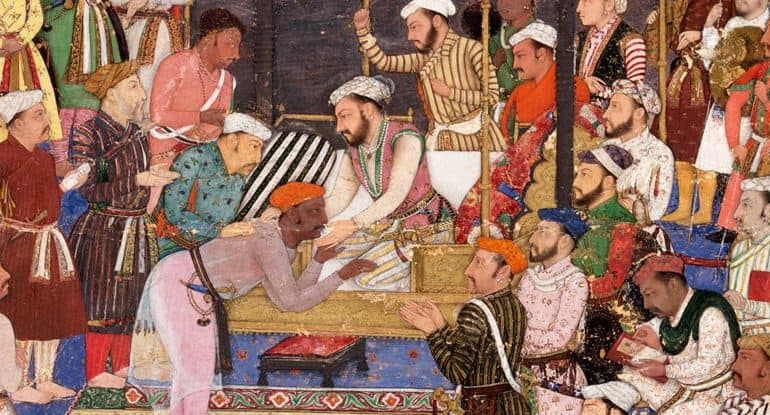

The history of courtesans in India is a story of shifting status. Once respected advisors to Mughal courts, they are now primarily seen as objects of sexual desire. This decline, from revered cultural figures to mere prostitutes, was likely influenced by British colonialism and the patriarchal structure of Oudh society. Notably, women’s contributions, both political and domestic, were often ignored or erased from history. This lack of documentation extends to Tawaifs, who were activists but were labelled as prostitutes despite their notable sacrifices.

The series holds immense promise, stretching across a significant period of nearly two decades, from the 1920s to 1947. While eight episodes offer ample room for development, the true strength lies in the visual spectacle. Every frame—from the opening shot to the finale—exudes grandeur. The costumes are breathtaking, the jewellery is dazzling, and the set design is a masterpiece. Director Bhansali’s signature style is undeniable. However, the narrative itself seems to falter, making the viewing experience less than captivating.

The term “tawaif” has undergone a significant shift in meaning. Once respected entertainers during a flourishing artistic period in India, they are now often associated with sex work in modern times. However, British rule led to their criminalization and social exclusion. Bollywood has long capitalised on the allure of courtesans. Films traditionally showcased their stories through suggestive dances and scenes. As India modernised, these depictions evolved from classical dances to more contemporary styles. Yet, the fascination with courtesans remained, with actresses viewing such roles as prestigious. These portrayals often romanticise the lives of courtesans. Lavish costumes and opulent settings create a fantastical world in films like “Devdas,” “Gangubai,” and potentially “Heeramandi.” This Hollywood-esque exotic depiction is far removed from the realities of these women’s lives.

A Lahore-based viewer raised concerns about the show’s historical accuracy. They argued that the portrayal of events, locations, and costumes doesn’t realistically depict 1940s Lahore. The viewer, identified online as Hamd Nawaz, shared their critique on X (previously Twitter). Their initial tweet stated,

“I just watched Heeramandi. I found everything but Heermandi in it. Either you don’t set your story in 1940’s Lahore, or if you do, you don’t set it in Agra’s landscape, Delhi’s Urdu, Lakhnavi dresses, and 1840’s vibe. My not-so-sorry Lahori self can’t really let it go.

Nawaz further criticised the show’s portrayal of language. They suggested that the creators relied on stereotypes by assuming an association between Lahore and a specific, highly poetic form of Urdu. Nawaz argues that this disregards the reality of the everyday language spoken in 1940s Lahore, which was likely Punjabi rather than formal Urdu.

A recent BBC report sheds light on the historical evolution of Hira Mandi through the eyes of a longtime resident. Ibrar Hussain, speaking to the BBC, described the area’s transformation across different eras:

Hira Mandi has witnessed many phases. It used to be different during the Mughal era; it transformed during the Sikh period; and then it changed again during the English occupation. And after the partition, it transformed yet again.”

He further elaborated on the current state of Hira Mandi, stating, “The government has now turned Hira Mandi into a food street. The women who used to live here moved out, and their families now live in various parts of Lahore. The bazaar was shut down in 1990, after which all the women who lived here left.”

Ultimately, Heeramandi stands at a crossroads. Will it prioritise spectacle over substance, perpetuating misconceptions? Or will it embrace the opportunity to offer a more historically informed portrayal of these fascinating women and their lost legacy? The series has the potential to spark important conversations about Heera Mandi’s complexities, women’s challenges, and the importance of recognising marginalised voices. If Heeramandi can move beyond the glittering facade, it could become a landmark series that educates and challenges audiences, leaving a lasting impact beyond entertainment.

Divya Malhotra

Read Also: DUB Review: Breaking Barriers with Brilliance:’Laapta Ladies’

Picture Credits: Y20 India