Language is a medium that allows us to communicate, identify, and express ourselves. However, this kind of expression, along with other social identities, usually results in systemic prejudice against particular communities. Whether it’s the language’s fundamentals, which reflect and reinforce gender binary norms, or its intersection with an individual’s religion, nationality, or place of belonging.

Religion, gender, and language are often categorised as the building blocks of an individual’s identity. Each of these factors influences a person’s beliefs, values, and perceptions of themselves and others. Often, discrimination based on religion, gender, or linguistic choices is seen independently; nevertheless, the confluence of gender and religion, as well as linguistic preference, has a significant influence on individuals and communities. While religion influences a person’s moral and ethical ideals, gender incorporates social and cultural expectations, and language both reflects and reinforces gender binary norms in society.

Religion & Language:

Language has always been a fundamental tool for portraying a religion. Whether it’s Arabic for Islam, Sanskrit for Hinduism, or Hebrew for Christianity, all of these affiliations stem from sacred texts written in these languages. Harold Schiffman in his book, “Linguistics, Culture and Language Policy’ explains that “One of the most basic issues where language and religion intersect is the existence, in many cultures, of sacred texts […]. For cultures where certain texts are so revered, there is often almost an identity of language and religion, such that the language of the texts also becomes sacred…”)

However, with the need for a separate identity, this linkage of languages tied to certain religions mutated over time. The shift in language of South Asian Muslims to Urdu, Hindus to Hindi, and Christians to English is an important example of this. This language shift describes how linguistic choices change as the need for a separate identity grows.

However, these linguistic freedoms quickly devolved into systemic discrimination against minority populations. Massive protests erupted at Banaras Hindu University (BHU) in 2020 over the appointment of a Muslim associate professor in the faculty of literature of Sanskrit Vidya Dharm Vigyan (SVDV). Protesters argued that a Muslim professor would be incapable of teaching Sanskrit, a Hindu language. NDTV writes, “The administration backed the professor. The panel that selected him, which includes Professor Radhavallabh Tripathi, one of India’s most eminent Sanskrit scholars, repeatedly said he(the appointed Muslim professor) was the most qualified candidate.”

Not only that, but hate campaigns and violence erupted in various parts of India in light of the use of Urdu in advertisements for ‘Hindu festivals.’ Nivedita Menon, a professor at the Centre for Political Studies at JNU, told Al Jazeera, “The Hindutva project sees Urdu as a ‘Muslim’ language. And invisibilising Urdu is part of the larger project of marginalising the Muslim community, in fact, physically eliminating it.” Linguists and historians contend that Hindi and Urdu evolved from ‘Khadi Boli,’ a dialect of the Delhi region, and are profoundly influenced by Persian, Turkish, Arabic, and Sanskrit. This hatred of a language because its identity is associated with a minority religion, despite its origins in India, highlights how segregation and systematic hatred towards minority religions are carried out through the use of languages.

Gender & Language:

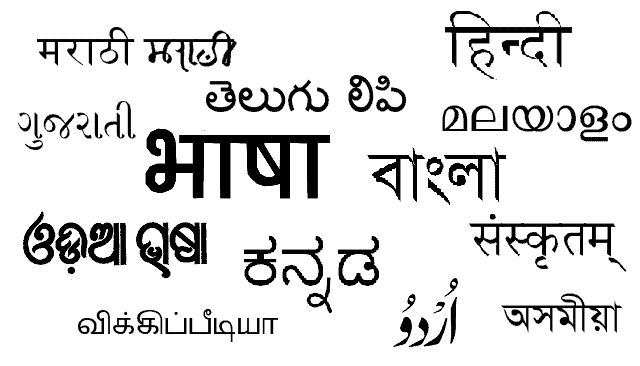

Languages reflect and reinforce gender norms and the gender binary. This has an intricate connection with the culture, religion, and history of the language. In recent years, queer activists and linguists all over the world have advocated for the necessity of gender-neutral terms. While some languages incarcerate gender in binaries, others prove gender’s presence outside of binaries by not gendering inanimate objects. While individuals assert that gender-neutral language is a Western concept, many Indian languages dispute this claim. Languages like Bangla, Assamese, Bhojpuri, Kannada, Angika, Maithili, and others do not limit gender into binaries, while Sanskrit uses masculine, feminine, and gender-neutral terms to refer to inanimate objects.

However, the most widely spoken languages, such as Hindi and French, do enforce binary. So, why are certain languages unable to use gender-neutral verb conjugation? While extra research is needed, basic efforts by native speakers of these languages may increase the possibilities of making these languages inclusive for everyone.

“On my first day of my bachelor’s degree, when I addressed myself as ‘hum’, my professor asked me how many people I am addressing with myself.”- Chandan Kumar, in an article by Youth ki Awaaz. This linguistic rigidity is a result of the Hindi belt’s class superiority. Hindi teachers must stop such rigorous pronoun implementation, and textbooks should be revised to include a discussion of gender outside of binaries. Another source of optimism is the use of second-person pronouns in Hindi. The usage of ‘aap’ while speaking to elders or as a sign of respect, regardless of gender, supports the idea that ‘aap is neutral and assuming someone’s gender is disrespectful.’ Aside from this, we can make our language more inclusive by not strictly categorising non-living things as masculine or feminine.

While language has the potential to bring people together, it can also be used to isolate and oppress them. While individuals argue that changing language to incorporate gender-neutral terminology is impossible since language represents history and culture, the development and shift to new languages by religious communities as the need for a separate identity emerged rejects this notion.

Read Also: Language and Patriarchy: The Case of Gendered Language

Featured Image Credits: Deccan Herald

Dhruv Bhati