Stepping into college often comes with high expectations about academics, friendships, and even politics. A rather ignored side of the college experience is the unexpected arc of self-discovery and growth that comes with it. This piece attempts to explore how college may challenge you in unforeseen ways.

I remember 2nd November, 2022, as if it were yesterday. Skittish with nerves but bubbling with excitement, I stepped into college for the first time. Like the hundreds of other freshmen, I could not wait to experience the much-anticipated college life.

We all have fantasised about our lives in college, props to the ‘wild’ college stories we’ve heard or the media we’ve consumed. The college experience is often glamorised and romanticised, becoming almost inescapable due to the ubiquitous college student trope in popular culture. Through all these narratives, we consciously or subconsciously end up building certain expectations about our time in college. However, one aspect of the college experience that we rarely foresee is how profoundly it will transform our identity. On my first day, I had a certain idea, an expectation from my three years at Delhi University. However, nothing could have prepared me for the journey I was to go through. A third year student of sociology at LSR shares a feeling similar to my own,

Since coming to college, I have realised that I have a newfound confidence in my ability to think for myself and make decisions completely of my own accord. Owing to all the discussions that we have had in our classrooms since the first year, I have become even hungrier to know more and to learn more. I feel I have become more fearless with my decisions, and I participate more comfortably and confidently in conversations as I have the right facts and ideas of my own,

One of the most dramatic shifts that we experience as teenagers is perhaps the transition from school to college. Suddenly, we no longer have to wear a uniform, no one is checking our notebooks, and we have a newfound autonomy. Many of us have longed for this freedom—this autonomy—but when it finally arrives, it brings with it a certain anxiety. Now we are on our own, and no one will be holding us accountable but ourselves. This sudden leap into adulthood can be quite jarring and challenging, but at the same time, the sense of independence and empowerment that it brings with it makes it worthwhile. Over time, we come to appreciate how some seemingly small moments have contributed to our growth and maturity. Another student from LSR resonates a similar feeling,

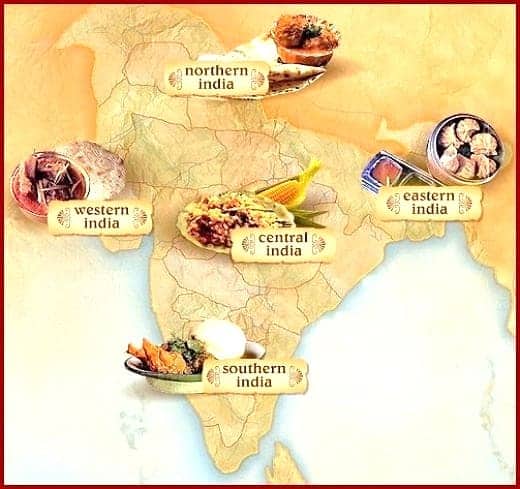

My time at DU has instilled a certain sensitivity in me regarding other people’s opinions and cultures, and I have come to appreciate being exposed to different ways of thinking,

While one can argue that there is still some work to be done on the diversity and inclusivity front of the university, it is not a stretch to say that being at Delhi University introduces you to people from very different social realities than your own, something that I find lacking in many other institutions, and particularly private ones. Students from markedly different socio-economic and regional backgrounds converge in their common pursuit of knowledge. These interactions challenge our preconceived notions and biases, prompting us to reflect on our own experiences and perspectives. This microcosm of empathy and understanding can then become a catalyst for positive developments in your personal identity.

In my own experience, engaging in conversations with people from diverse backgrounds heightened my political consciousness. I found myself more involved in socio-political discourses and issues. While I do recognise that my thoughts or actions alone may hold little value in comparison to the gravity of the socio-political issues, I do not feel as powerless as I once did. I now have a voice, even if it may not be as loud as others. This realisation has also made me more comfortable expressing myself unapologetically, whether through conversations, fashion, or art. A third-year Economics student from Gargi College remarks,

Before coming to college, I was a shy kid. I didn’t speak unless I was spoken to, and sometimes I even tried to escape regular conversations. I anticipated that my college life would be similar. Thankfully, that wasn’t the case. These three years transformed me from an introverted kid to someone who makes small talk in the metro now,

While the prospect of finding connections in college may seem daunting, these shared spaces and daily interactions make it easier. For many of us, college becomes a place where we find a community and a sense of belonging.

From navigating administrative tasks to participating in student politics to daily commutes, every small experience in college contributes to the transformation of our identities. To anyone who’s just about to start their college journey, here is an unsolicited piece of advice: take a deep breath and strap in, for the next three years just might surprise you in ways you never imagined.

Read also:

Maintaining your Identity in College

Featured Image Credits: Disha Bharti for DU Beat

Disha Bharti