Baffling exit polls and puncturing the Congress complacency, the BJP has battled anti-incumbency to secure its third term in Haryana. An inordinate number of dissidents, glaring portents for division within the party’s central leadership, a failure to foreground fresh faces and an unsubstantiated socialist rhetoric, inter alia, have come together to form, what seems to have been an insurmountable impediment for the Congress. Maharashtra and Jharkhand no longer appear as welcoming.

The Congress has thus far failed to diagnose the rot in its strategy. Its narratives involute upon themselves, constantly miscarrying with the public, and its parroting of the same old defeated stratagems now heads ad nauseam. The Haryana defeat carries with itself considerable ignominy for the Congress which has been smug in its prophecies of victory before and the natural course of the ensuing result has been invariably failure. While Congress president Kharge denies that the Maharashtra assembly elections shall be affected by the defeat, the BJP and its allies remain confident that the ruling Mahayuti in Maharashtra has been only further strengthened. It is implausible that the long-enduring, anti-incumbency temperament shall so suddenly flip, which leaves room to investigate what the BJP has done right during the campaigns and on-ground.

Primarily, a deluge of rebel candidates have fractured the Congress’ vote bank, drawing from it a generous amount it could have used against BJP. The INC lost 16 seats to rebels and independents, severely weakening it against the BJP’s far more structured and organisationally sound ticket management, particularly after UP in the Lok Sabha elections.

The following table illustrates the Congress’ losses to dissidents:

| Kalka | Congress lost by a margin of 11k votes (Rebel got 32k votes) |

| Pundri | Congress came 3rd; Congress rebel got 40k votes and lost by 2k. |

| Rai | Lost by a margin of 4.5k votes (Rebel got 12k votes) |

| Gohana | Lost by a margin of 10k votes (Rebel got 15k votes) |

| Safidon | Lost by a margin of 4k votes (Rebel got 29k votes) |

| Dadri | Lost by a margin of 2k votes (Rebel got 6k votes) |

| Tigaon | Congress came 3rd; Congress rebel got 57k votes and lost by 37k votes. |

| Ambala Cantt. | Congress came 3rd; Congress rebel got 53k votes and lost by 7k votes. |

| Assandh | Lost by a margin of 2k votes (Rebel got 16k votes) |

| Uchana Kalan | Lost by 39 votes (Rebel got 32k votes) |

| Bhadra | Lost by a margin of 7.5k votes (Rebel got 27k votes) |

| Mahendragarh | Lost by a margin of 2k votes (Rebel got 21k votes) |

| Sohna | Lost by a margin of 11k votes (Rebel got 70k votes) |

| Ballabgarh | Congress came 4th; Congress rebel came 2nd, receiving 44k votes and lost by 17k votes. |

| Dabwali | Lost by a margin of 610 votes (Rebel got 2k votes) |

| Rania | Lost by a margin of 4k votes (Rebel got 36k votes) |

| Bahadurgarh | Congress rebel won the seat as an independent; Congress candidate came 3rd. |

Further, the Congress made no attempts to restructure its leadership. The young faces—Selja in Haryana and Sachin Pilot in Rajasthan—were conceded to the older ones, of Hooda and Gehlot respectively. The pattern makes itself manifest with an octogenarian as the party president. The BJP, on the other hand, deployed 60 fresh faces to stand against the ancient heavyweights, albeit losing ones, of the Congress. The Congress renominated 17 of its stale candidacies that had lost in the past. The 2023 state election Telangana win for the Congress, supplanting the previously incumbent Bharatia Rashtra Samiti, came in only after they took a chance with a new face – Revanth Reddy’s.

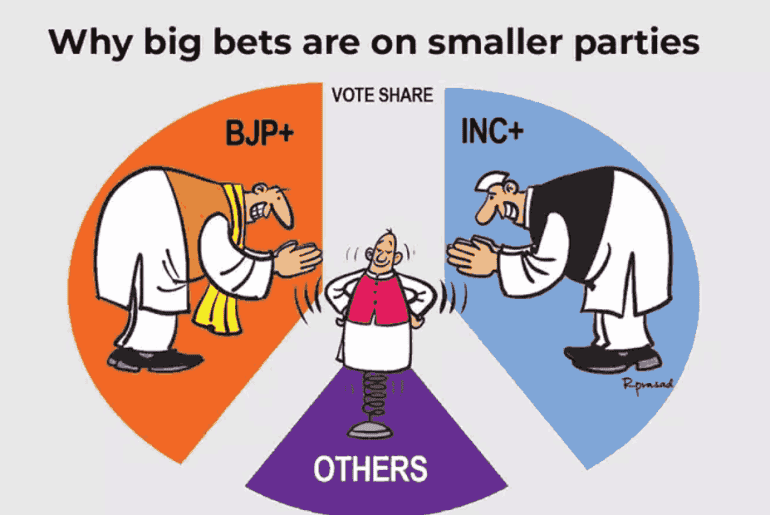

Congress also almost consciously defined itself as a ‘one-caste party’. The Congress’ overdependence on the Jat population proved to be a fatal oversight. The BJP conquered the Congress’ meek share by consolidating the 75 percent of the non-Jat population. Congress’ implicit preference for Hooda to Selja handed to the BJP critical accusatory ammunition, allowing them to charge the Congress with anti-Dalit sentiments and a neglect for the non-Jat population. Even the Jat votes, that the Congress hoped to completely own, had to be shared with INLD, further increasing BJP’s uncontested share of the non-Jat votes.

Despite the Congress’ efforts to appeal to the OBC demographic, comprising 40 per cent of Haryana’s population, BJP’s Saini clearly won the affection of the masses. Ajay Singh Yadav, chairman of the AICC OBC Congress, himself confessed to the Congress’ disregard for the OBC belt in Haryana. The CSDS-Lokniti survey reports the strength of the OBC population in favour of the BJP. The OBC support flourished after Saini replaced Khattar as chief minister. The BJP managed to assimilate into its supporter base a “rainbow coalition” of Brahmins, Punjabi Khatris, non-Jatavs, Yadavs and SCs. The “Lakhpati Drone Ladies” project engendered a massively positive reception of the BJP’s attempts to “elevate the SCs to general status”, in the words of an ITI student from Ambala.

The Gandhi siblings campaigned with much pomp, but rather late. The BJP’s strategy had been to counter the anti-incumbency silently and aggressively. The Congress’ work assumed tangibility too late, and in that they have not defeated the image, one needing much redressal, of the relative passivity of the party and the unattractive languor in its reactions. RaGa’s flimsy socialist narrative did not help their case with the upwardly-mobile social classes as well as the urban votes.

Analysing Congress’ trends, juxtaposed with those of the BJP, it remains a matter of irrefutable truth that the ability of the BJP to counter is what keeps its power from waning. Given the BJP’s untarnished dominance, only in terms of its claims to power and occupation of office, it is peculiar that the Congress keeps succumbing to its flippant confidence in its, in all honesty, paltry chances to overthrow the Saffron Goliath. What blights this torpid David and wherefore does he hibernate? One cannot help but nod in terror as they ponder the truth of Modi’s tirades when he warns of the “chaos” that a Congress government shall bring.

Read Also: Phogat’s Haryana – A changing political landscape

Featured Image Credits: PTI

Aayudh Pramanik