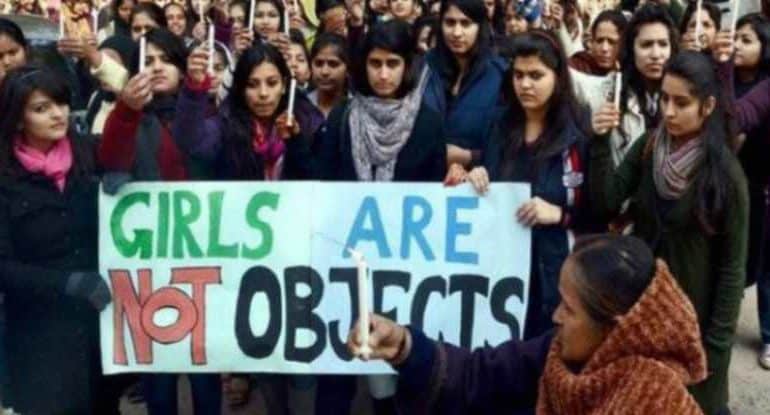

The discourse surrounding cricketer Hardik Pandaya’s divorce from his wife transcends the bounds of mere gossip, shining a spotlight upon the undercurrent of misogyny in the cricket fanbase.

When cricketer Hardik Pandya and actress Nataša Stanković announced their divorce, as expected, it became the new fodder for a gossip-hungry audience that thrives on playing authority on people’s private lives. The media coverage and reaction, however, extended beyond the scope of typical gab, morphing into a smear campaign against Nataša, who became the target of much vitriol and trolling.

While Hardik’s social media was filled with comments expressing love and support during a tumultuous time, Nataša faced a tirade of hate comments listing every misogynistic slur in the book. Gossip pages posted unbased rumours regarding alimony, pre-nuptials, and custody that painted her in an unflattering light. Meme pages made her the new face of “women☕”. Her past relationships, her work as an actress and a model, her appearances and absences at cricket matches, her interviews, her social media activities, every detail of her past and present was dissected by a fervent audience eager to criticise.

Despite the fact that none of us know what happened between the couple, people had already decided who was to blame. Even though the divorce is a non-penal legal matter, the court of public opinion had already chosen its criminal. And of course, it was the woman.

This is not an isolated incident, but sadly just another example in a long history of cricket fans targeting women with unwarranted hostility.

The wives and girlfriends of the cricketers are often subject to vicious rumours and scrutiny regarding their true intentions. Every action of theirs is put under the magnifying glass and pulled apart. The sentiment of “she doesn’t deserve him” is echoed by both fanboys and fangirls.

Even the weight of the performance of the team falls upon their shoulders. Recently, the then Captain Virat Kohli’s poor performance at the ICC World Test Championship Final 2023 was blamed on his wife, the actress Anushka Sharma, with people claiming her presence to be a distraction for Virat, and labelling her as a jinx for the Indian Cricket team. Being the wife of the Captain and being a successful public figure of her own has often put her on the receiving end of such revulsion. In 2015, her effigies were burned in public demonstrations after Team India’s defeat in the semi-finals of the ICC Cricket World Cup.

Match losses result in the female friends and family of the team being bombarded with abuses and threats. These threats are even levelled against the minor daughters of the cricketers. In 2020, rape threats were made against cricketer Mahendra Singh Dhoni’s then 5 year old daughter Ziva after his team lost a match. This behaviour is not just reserved for the women linked with the Indian cricket team, but also extended to the women linked with the winning international team. After Australia’s win against India in the 2023 World Cup Final, pharmacist Vini Raman, wife of cricketer Glenn Maxwell took to social media to request a stop to hateful messages, stating

“…and cue all the hateful, vile dms… take a chill pill and direct that outrage towards more important world issues ”

While the women associated with male cricketers are given undue negative attention, the women who play cricket themselves face an entirely different form of neglect—one marked by a lack of public attention and support. Despite the undeniable talent of the Indian cricket team, and even when they perform better than their male counterparts, women’s cricket remains widely unpopular. While the names of male cricketers, both current and former, are household names known by children and elders alike, the names of the women bringing pride to India on an international scale remain faded in obscurity. Men’s cricket simply being known as “cricket” while women’s cricket having to add the “women” prefix, is a glaring indication of how women are considered othered from the game.

The accomplishments of female cricketers are also often considered secondary to their appearances. Retired Captain Mithali Raj holds numerous world records in the field of cricket, such as being the first player to score seven consecutive 50s in One Day International matches and being the player to score the most runs in women’s cricket. Despite these ground-breaking achievements, she has often faced slut-shaming for her clothing choices. The physical form that enables her to win accolades for the country and its people, is the same womanly body objectified and judged by said people.

Cricket is not just a sport in India. Popularly known as the unofficial national sport, it’s entrenched into the very cultural fabric of the country. The joviality and enthusiasm it generates amongst the people is unmatched by any other phenomenon. Cricket season brings forth a great cause for patriotism and celebration for the public. A large part of the population however remains somewhat gatekept from it. From hate campaigns against the so-called “WAGs” to sidelining of women’s cricket from the mainstream to random men taking it upon themselves to test the knowledge of female fans on the subject, the widespread misogyny within the fanbase makes it a less welcoming space for women.

As cricket continues to rule over the hearts of Indians, it is essential for a healthier society that the community surrounding it becomes inclusive and supportive of women both on and off the field.

Image Credits: Times Now

Read also: C for Cricket and C for Controversy

Samriddhi