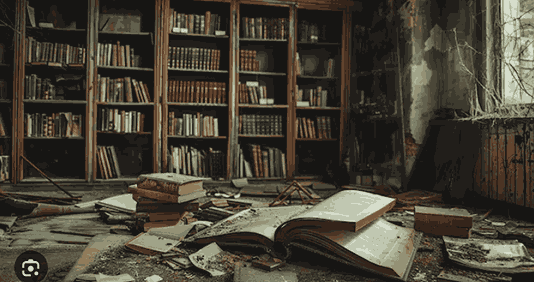

The hands of the clock now beckon you home and you realise you are quite far away. As you step across the threshold of your motherland, you do not recognise it anymore. The universities are now debris, the art nowhere to be found and the citizens asleep immobile, in a deathly slumber.

On the asphalt streets of Bengal, there is God. Amidst the wet mud underneath newborn rice; in the dramatic torrents from precariously placed Dhunuchi on sundried hands; in the kitchen’s sweating, simmering air and the tear that sizzles in the onion sliced open on the cutting board, there is God. From the ancient, blistered pages of a chalky hardbound Thakumar jhuli, Thakuma’s thunderous and meek voice rings clear and God flashes her third eye. When you hear her, you hear the underbelly of a tidal wave roar with ripe and red age – her seasoned drawl trembles like the quaking earth. Sitting a few trees, a few cities and a few seas away from her, you find that all around you, the wet mud, the dhunuchi, the curry that stained your childhood nails have crumbled to stone.

You are not home. The air is no loner laden with the heady fragrance of dawn Shiuli, the paint no longer peels off walls as your eyes fall to the floor and the sunlight no longer burns with the force of a thousand furnaces in your face when you smile. You feel estranged from language for your tongue has remained in your mother’s heartland. There are no trams here, no yellow taxis, no cobblers spread out on street corners, no purple skies of the Kalboishakhi, and no roads choked with rice lights and kabiraji during pujo. There are no little gods in melting make-up darting about on the streets, touring the city on shoulders and veined, brown laps. There is no you.

Thus Modhushudon says,

“সাধিতে মনের সাধ,

ঘটে যদি পরমাদ,

মধুহীন করো না গো তব মনঃকোকনদে।

প্রবাসে দৈবের বশে,

জীব-তারা যদি খসে

এ দেহ-আকাশ হতে, – খেদ নাহি তাহে।”

This translates to:

“If disaster befalls,

My questing heart,

Do not banish me from the nectar of your memory.

If, by foreign banks,

My life cascades away from me,

I do not fear the death of my body.”

For the Bangla that has seeped through the fissures of Bengal and carried an exodus of the personality to the without and ushered them within, through the crests and troughs of an experience divorced from the comfort of a motherland, for the teeth watered with the acrid wind of a foreign song, Modhushudon lamented. Of course, along with departure, there must be an arrival. But we realise that the arrivals pale soon. That which arrives and has arrived, could not arrive again. In its incomplete arrival, an arrival is effervescent. There is another arrival and we lurch forth, perpetually, towards newer lands and tongueless elegies sung in deserted rooms. This sense of the ceaseless arrivals is only an abstract account of the idea of the present. Aristotle had reductively expounded it as an uneventful translocation between tactile distances. “Duration is the stuff of which conscious existence is made”, Bergson shall profoundly declare some two centuries and two score years later. But I digress. Why this lived time is important to understand is because it corresponds to the Bengali’s distorted lived identity.

This precipitates the workings of an abstract nation that is peripatetic and exists in the blank space wrought by a disturbed people’s diaspora. How did this come to be? Indeed, the political unconscious, as Jameson would observe, of the endless literature that Bengal could offer, reflects the change in the most confounding manner. It is not easy to say when the left front began to collapse; the artistically, academically, and pedagogically peerless British-fed empire of the paddy fields commenced a burgeoning descent to an industrial, infrastructural and economic impasse. Of course, the united Bengal, alongside the other, now prominent, port cities of colonial India’s Madras and Bombay, stood to be the entrance of the British into the Indian subcontinent. The colonial landslide was inevitably felt the strongest in these cities. The domain of English academia is still, to this date, dominated by either the present-day south-Indians or the Bengalis. It is no coincidence for such to have been the case. Bihar, which was an organ of united Bengal, produces the fiercest administrative officials.

It does not take the exceptionally precocious to piece together the facts. I must confess that I have also met that crude populace that has failed to tag this failing state machinery. It was only yesterday that I had the misfortune – now, let this not be extrapolated so as to deem their company unpleasant, indeed it was the converse – of acquaintance with a certain professor who was astonished at my decision to have chosen Delhi for my undergraduate destination. Being from Kolkata, why had I not chosen amongst the premier institutions of the city? Her question was not unfounded. Two decades back perhaps, or a little more, I would have considered it. In fact, it would not have been an easy task gaining admission into either Jadavpur University or Presidency. “No one knows what happens during the checking of Jadavpur entrances anymore”, sighs a Professor that I know. I would also have been assured that the evaluation of my entrance examination at the former would have been a fair one. Nevertheless, the unnamed was unaware, albeit, not blissfully so, of the cruel edifice of Bengal’s present truth. When I asked my friend who is currently a second year student of Mathematics at Presidency what has become of the education system in Bengal, what it is that has so dramatically altered its state machinery, and he said “Bengal has once churned out nobel laureates like the primed barrel of a gun; we have fallen far since then. The culture where Bengali households still push, sometimes excessively, their children towards unimaginable heights of success still exists. But the means for our generation to manifest that now-distant dream have been lost. We see them only reminisce, complacent and smug in their erstwhile glory and do nothing to reclaim it.” It might sound scandalous to say so, but it is my belief that any Bengali, with a morsel of ambition remaining in their blood, has left. The evil of the Naxalites, which had catalysed this transformed political sub-space in the first place, has been replaced by the evil of stagnancy that is borne of negligence and a ruthlessly debauched moral compass. This moral compass does not remain confined to the rulers of the state only, for we must remember the citizenship that has advocated for them, and handed to them this power. It would be folly to discount the sheer comprehension of the people’s pulse, of which the incumbent opposition ruler seems to be in dangerous possession. She knows what makes Bengal tick and she makes them tick well. I am afraid that if I indulge myself any further, I shall stand to lose my diplomatic tenor and therefore I shall not risk that venture.

Bengal has been outpaced, and superseded by time, for all great societies are fated to fall. This is not to occasion a trite exchange, only to ascribe the causality of a devastating truth to powers intangible. And yet, I must maintain that it is not, in fact, intangible. The democracy of the Indian subcontinent is now choked with choices that one could not make without the mortifying acceptance of their choosing the lesser evil. That is another complicated tangent of debate, which I could not take up frankly without gravely endangering myself. We can no longer jointly hail one as a scholar and a politician. That species seems now to be extinct. In any case, as I grapple with this undeniable prospect, it is quite clear to me, a state I hope I have been able to confer upon the readers of this article, why the exodus has been in such Herculean proportions. The issue of the brain drain is not atypically Bengali. In Bengal, the tremors have been felt deeply, and yet, to the perspicacious, that the drain is quite Pan-Indian. The established Indian scholars have all to sport in their resumes, a degree earned from abroad. This is not simply the result of a quest to expand one’s horizons, as seems most apparent. The outward-bound instinct, or Beauvoir’s masculine transcendence, is not a universal tendency. I would fail at this moment to furnish the reader with the statistics, but commonsensically, it would not be preposterous to infer from cases of those irrefutably successful, that ambition is not a rather ubiquitous quality if all the world’s sensibilities were to be accounted for. If the reason so posited, about expanding one’s horizon, were true, then how does one explain the negligible immigration that India has seen recently, in terms of students. Of course, it is a developing country, and yet, if one were to examine the history of Indian scholars who have flourished abroad, one must concede that the Indian education system was once robust and globally revered. It pains me that I cannot account for a solution that does not drastically alter the system, and perhaps I must not. Perhaps it is important that the system be so radically reformed, for if we continue along this path, we shall only gracefully expedite our world’s transmogrification into the dystopian world of Orwell, if not extinction.

Read also: Of Remembrance and Letting Go: An Ode to Hometowns

Featured Image Credits : Ahmadzada for Freepik

Aayudh Pramanik