Ahead of our 75th Independence Day, here is looking at the four unsung verses of our national anthem by a fellow Bong and his experiences with the same

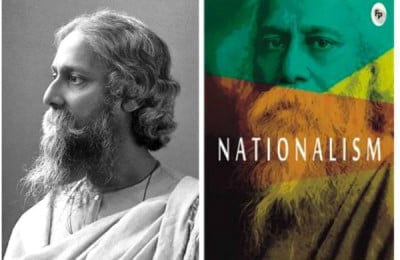

Growing up in a Bengali household, Rabindranath Tagore or “Kobiguru” (the guru of poets) as we were so fondly taught to call him, was a looming presence in my life. The drawing room wall had a two foot long portrait of the man with his cascading white beard and saintly eyes. On summer afternoons legs propped on the divan and orange peels on my fingers next to undone algebra I could hear him walking past the still curtains – his presence speaking of a quietude so deeply internalised that it could almost be akin to silent absence. On monsoon evenings when my heart was too heavy, his poetry gave words to my unshed tears. And on Independence Day, when I heard the country blaring the national anthem in a hindi dialect far removed from the original bengali pronunciation my heart would swell with anger.

In crowds, from childhood, I made it a point to sing the anthem in the Bengali dialect, while people around me would turn and stare at me with glaring eyes – indicating that I was the person who was singing it wrong. “Don’t be a rebel without a cause, of course there has to be a standard pronunciation for the entire country,” my mother would say each time I would go on an unwarranted rant about the hegemonic imposition of the hindi dialect across the nation. But little did I know that this was just the tip of the ignorance for most outside the Tagore-centric cultural bubble of Bengal.

In the middle of a casual video call with some of my recently made friends in DU, I found us humming the anthem after hearing a spectacular orchestral arrangement of the same on Youtube. But it was only when I continued to sing, long after the verse had ended that my friends curiously asked me as to what I was singing. That night I spent close to an hour, explaining to my friends, all from various ends of the country, how the national anthem is merely the first verse of a five verse long song composed by Tagore. It is with their shocked faces in mind today, that ahead of the 75th year of our Indian Independence, I present to all my readers the four unsung verses of the song from which our anthem originates. The translation will never be at par with the original Bengali and hence apologies are in order for all that will inevitably get lost in this humble translation.

Original Bengali:

Ahoraho tabo aahwan procharito shuni tabo udaar baani

Hindu bouddho joino paarsik musalmaan khristani

Purabo poschimo aase tabo singhasano-paase

Premhaar hoy gnaatha.

Janogano-oikyo-bidhayako jayo hey bhaaroto bhaagyo bidhata !

Jayo hey, jayo hey, jayo hey, jayo, jayo, jayo, jayo hey.

Paton-abbhudayo-bondhur pantha, jugo-jugo dhaabito jaatri

Hey chirosaathi tabo rathochakre mukhorito patho dinoraatri.

Daarun biplab-maajhe tabo shankho dhwoni baaje

Sankatodukkhotraata.

Janoganopathoporichaayako jayo hey bharoto bhagyo bidhata !

Jayo hey, jayo hey, jayo hey, jayo, jayo, jayo, jayo hey.

Ghorotimiroghano nibiro nishithe pirito murchito deshe

Jaagroto chilo tabo abichal mangol natonayone animeshe.

Duhswapne aatonke rokkha korile anke

Snehomoyi tumi maata.

Janoganodukhotraayako jayo hey bharoto bhagyo bidhata !

Jayo hey, jayo hey, jayo hey, jayo, jayo, jayo, jayo hey.

Raatri probhaatilo udilo robichchhobi purbo-udayogiribhaale –

Gaahe bihangamo, punyo somirano nabojibanoraso dhaale.

Tabo korunarunoraage nidrito bhaarato jaage

Tabo charone nato maatha.

Jayo jayo jayo hey, jayo raajeswaro bhaaroto bhaagyo bidhata !

Jayo hey, jayo hey, jayo hey, jayo, jayo, jayo, jayo hey.

Translation

Endlessly resonates thy charitable call to uplift –

Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains, Parsees, Muslims and Christians.

Across the East and West, unites this call, in strings of love.

You, the one who binds together the people in unity,

The one in whose hand sways the fate of India

Hail to thee!

Reflected in the wheels of your chariot O! the Timeless One,

On the jagged road of crests and troughs, walk a million listless.

In the midst of astounding rebels, rings loud your clarion call to revel –

You – the one who quells evil and distress!

Hail to the thee, the hand who sways the fate of India

And who shows its millions the path to traverse!

In the expanding gloom, of the darkest nights of distress,

Was awake forever, your bent unblinking gaze.

In the darkest of dreams, in the direst of circumstances,

You held us in your embrace –

Like a piteous mother to her babe.

Hail to thee, the hand who sways the fate of India

The one who vanquishes the distress of our souls!

The night melts into day, and rises the sun

On the eastern horizon front

Sing the birds, swayed by the holy breeze,

Tunes of a new life impending.

To your blood marked songs of compassion

Answers a nation rising from slumber,

Bowed forever at your lotus-feet.

Hail to the thee, O! Mightiest of Rulers,

The one in whose hands rest forever, the fate of India!

Here is a rendition of the song from the 2015 Bengali film Rajkahini (A Tale of Kings)

Anwesh Banerjee

[email protected]