What makes the works of Saadat Hasan Manto, from over 60 years ago, a significance for the education of an Indian, of a human today?

From the morning newspaper to the prime-time debates, the average Indian is fed a healthy diet of hypocrisy, hegemonic morality, and jingoistic nationalism while the truth of those in power and that being done through power is marred to produce a confused Indian, at best. College education in a nation like ours is in a dire need of a sense of revolution, which teaches us the choice of what to be and how to be, by showing us what not to be. A mirror to look at our identity as ‘Indians’, as nationalists, as products of the society that builds and breaks us normatively, as humans, is needed.

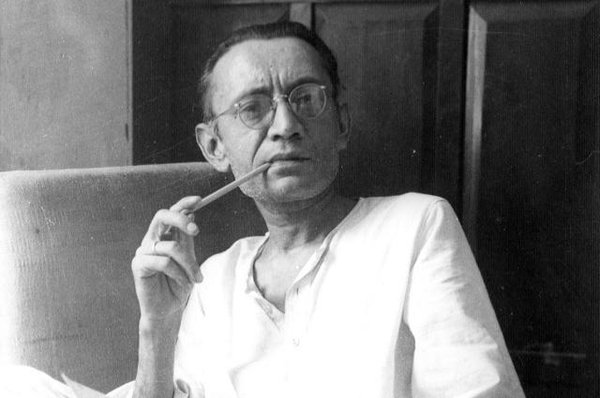

Enter a man from the 1940s, clad in a kurta, holding a smoke in one hand, an unflinching truth in the other, capable of jolting us into the public sphere of uninhibited discourses, yet taking us home more than anybody else can and anybody else should today. The greatest misconception about this man- Saadat Hasan Manto- a private literary movement for the writer of this piece, is that he wrote obscene stories that do not do justice to the parameters of what makes ‘good literature’.

“It is very ironical that none of his writings have found a place in these (school) textbooks. I have read Urdu for 15 years and yet I haven’t found a single story of Manto in any of the textbooks. Being a student of Urdu, I think what distinguishes him from the rest of the writers is his courageous writing. Most of Urdu literature is filled with romantic stories but Manto writes in an unconventional way. He does not shy away from detailing love-making scenes which got him into a lot of trouble,” shares MaknoonWani, a second-year student pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism from Delhi School of Journalism.

Tried for obscenity six times, Manto took great pride in his literary prowess, but his prowess today lives on because he showed that a story need not be ‘decorated’ to paint hope, to represent, to defend or to prove, in order for it to stay with you. “Manto’s writings reflect the actual rawness of life in the truest sense. Shattering and spirited, all at once,” says Kartik Chauhan, a first-year student of English at Hindu College. It can be the closest reflection of ‘what is’, like the reality of a time peeling the layers of a conscience he assumes in his reader, burying itself forcefully, without permission of the owner, in the core of your being.

Shaurya Thapa, a second-year student of History at Hindu College, supports this by saying, “Manto might not have the most perfect language compared to other writers of his era but that’s what makes him different from the rest. His writing style was more direct and hard hitting, he didn’t have to have a polished tongue always because his times were surely not. In some stories like the Dog of Thitwal, you can say that he mastered magical realism. Added to that, there’s no doubt Manto can also be regarded as a master of modern horror- in a realistic, grittier sense, Thanda Ghosht and Khol Do being major examples. The very fact that reading Manto makes me uncomfortable shows how powerful his stories were.”

Where Pinjratod has to press to the authorities its right to autonomy, demanding an eradication of discriminatory and oppressive practices of curfew in the year 2018, Manto’s women ran naked over 60 years ago. Many object to the representation of women in Manto, expressing that there is a sexual objectification he endorses in his works. But only when one reads the text he writes, leaving judgement and preconceived ideologies of morality behind, does the realisation of his honesty occur. From a legacy of work, it is foolish and hasty to pick one section out in isolation of everything else and call it unfeminist. His women talked about underwears, religion, prostitution, alcohol, violence and sex in a way that did not define them in totality. He represented them as agents of their own mirth who acted, and must possess choice and control of their individuality. Manto’s women were humans, not metaphors or conduits for another entity or phenomenon.

“If you cannot bear these stories, then the society is unbearable,” Sa’Saab would often say within his circle and in his numerous testimonies at the court. Taught from the western ideals of Plato’s Republic, students in India should pick up Saadat Hasan Manto to look at the muddle of a society that birthed their conditioning, at every point of time. His descriptions, never prescriptive in their great simplicity, bring to you the India before and after 1947 that remained, and the destroyed.

Sharvi Maheshwari, a third-year History student at Miranda House, strongly believes that Manto was way ahead of his time, haunting people because of his rawness, and comments, “Toba Tek Singh makes people realise that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a serious issue.” His personal life deteriorated in the awareness of the times that governed the post-partition India, and parted from his beloved Bombay, his writing lost embellishments, if they ever held any. His lens lives today in the unapologetic courage of his pen.

A thid-year student pursuing BA (Honours) Humanities and Social Sciences at Cluster Innovation Centre, Niharika Dabral says, “The first (and only) story I read by Manto was Khol Do and it haunted me. I didn’t pick Manto again.” It is this unrest and the ability of Saadat Hasan Manto’s words to haunt the readers which makes his literature significant in a time where every statement made is under the threat of brutal censorship. For students to be out on the streets, questioning, fighting, wanting to change and be free, it is an urgency to shudder through Manto’s truthfulness.

Saadat Hasan Manto said, “I feel like I am always the one tearing everything up and forever sewing it back together.” In his 42 years, from struggling for twenty rupees to engaging in mehfils with Ashok Kumar and the who’s who of Indian cinema from the 1940s, he did live a life of creation and annihilation through words and the violence around his words. He was neither a victim nor an activist. Manto was a writer, whose words did not run afraid of time and truth. He never held the onus of teaching the society how life must be lived, but he wrote enough for his readers, years past he has been gone, to see the truth and the choice we can make in our truth.

Image Credits: Wikimedia Commons

Anushree Joshi

[email protected]