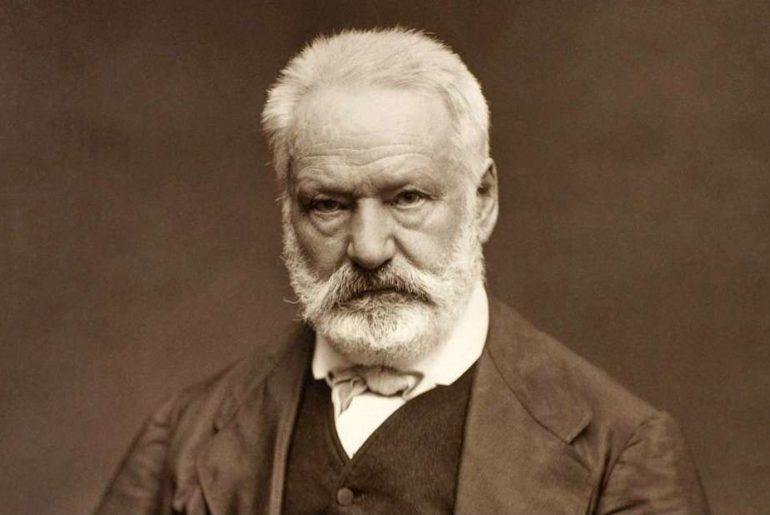

As we celebrate the 216th birth anniversary of one of the greatest novelists of all times, our correspondent takes you through a stroll of his life and what exactly made an aristocrat come with the greatest texts on the million shades of exploitation and poverty.

In a letter to M. Paul Meurice, a cordial friend of his, dated in December 1880, five years before his death, and almost 18 years after the publication of Les Miserables, Victor Hugo (1802-1885) writes,

“It is with deep emotion that I tender my thanks to my compatriots.”

“I am a stone on the road that is trodden by humanity; but that road is a good one. Man is master neither of his life nor of his death. He can but offer to his fellow citizens his efforts to diminish human suffering; he can but offer to God his indomitable faith in the growth of liberty”

To examine the significance of the philosophy and hermetic sentiments being reflected in these lines one needs to fall back to the ideologies in which he was nurtured as a child, and ponder over the trends of his political stints and writings. Despite being born in royalty, he was not always destined to be the champion of the average frenchman and the socialist these lines established him to be. What made the crowd of his times shout “Vive Victor Hugo! Vive la Republique” in the same breath requires substantial pondering to testify our reverence for a man whose every action commands our admiration and respect; for the writer who has infused new life in the antiquated diction of our literature; for the poet whose verses purify while they fascinate the soul; for the dramatist whose plays exhibit his sympathy with the unendowed class; for the historian who has branded with ignominy the tyranny of the oppressors; for the satirist who has avenged the outrages of the conscience; for the orator who has defended every noble and righteous cause; for the exile who has stood up undaunted to vindicate justice, and finally, for the master-mind whose genius has shed a halo of glory over France, requires a delve in countless pages of literature.

His father, Joseph Leopold Sigisbert Hugo was born in Nancy, France. He was enrolled in the french army at the minor age of fourteen years. Victor’s parental side may, without exaggeration, be described as a race of heroes; five of his brothers were killed during the wars of Revolution, the sixth became a major in the infantry while his father rose to the rank of a general in the army of Napoleon Bonaparte the first. The ideals of his father, thus, were that of a freethinking republican who considered Napoleon a conquerer. His duties very frequently took him into Nantes, where he became acquainted with a ship owner named Trebuchet, who had three daughters, one of whom, Sophie, soon stole captain’s heart, and became his wife. In a stark contrast to the ideologies of her husband, Sophie Hugo was a Catholic Royalist who was romantically involved with General Victor Lahorie, executed in 1812 for plotting alongside Moreau against Napoleon. Victor writes in his memoir about Lahorie,

“Child!, he would say to me, while expatiating on the Roman Republic, “Child, everything must yield to liberty.”

The mother followed the father in the initial days of Victor’s childhood through his campaigns in Italy and Hugo and learned much from these travels, but this soon was minimised when Sophie settled in Paris in 1803 with the children, when Victor was just one year old. Her relentless affection and care for Victor extended to his education. The basis of her teaching apart from being vehemently Vendean Royalism, as one of her contemporaries has remarked, with elements of Voltairianism, with a woman’s positivism, however, did not instil into her son the doctrines of any special creed. Later, Victor Hugo himself writes,

“Certain it is that the brains of children imbibe the ideas of those that bring them up. Parents and tutors have a fertile soil wherein to show the seeds of prejudice, which, developed by education and matured by love, become the giant plants of which the man full grown and reasonable will have unbounded trouble to dislodge the roots.”

The period that followed was of the fall of the empire, as the Napoleonic forces conceded to the Bourbons, reinstating the monarch’s “by right divine.” To Madame Hugo, the fall of the Empire was a satisfaction and she did not endeavour to curtail or disguise it. However, in the view of Victor Hugo, a lad of twelve, it seemed at first as if France must have sustained a humiliation in coming down from an emperor to a king. He had always felt a certain amount of admiration for the great Buonaparte, but his mother’s training, combined with that of his priest tutor Pere Lariviere, had prepared him to love royalty, and accordingly he was ready now to love it with all his heart. Subsequently, it would be his father, who, as a veteran, and his later monumental life experiences, would influence his mind towards republicanism.

Victor Hugo’s belief in the ideals of Monarchy faded fast, but nevertheless, his trust in the institution remained more or less unaltered. Hugo began planning a magnanimous novel about social misery and injustice as early as the 1830s, but the dream of Les Miserables was not to be realised until 1862. Hugo was perfectly aware of the magnitude of his undertaking. At the age of twenty-one, reviewing a novel by Walter Scott, he called for a new type of fiction that would give an epic scope to the moral and social consciousness of his period. Years later, as he approached the writing of Les Miserables, he wanted more than ever to achieve a fusion of an epic with dramatic elements. Such a synthesis, he felt, was the proper business of the novel- that new and unique literary phenomenon which was also a powerful social force. At the end of his career, surveying his own words, he was more than ever convinced that the novel- his kind of novel- was a drama too big to be performed on any stage.

The power and scope of Les Miserables was terrifying- not only to the audience but also to the author. The novel developed a whole new insight in the atrocities of the noble class and the ruling institutions, the interpretations of religion, duty, and faith, and the crisis of existence at the hands of perpetual poverty. The stories of Fantine, Valjean, Cosette, Javert, Marius, Gavroche and the Thenardiers have repercussions way beyond the mundane ideas of resemblance to reality or departure from it, and Les Miserables is quite clearly the greatest contribution of the French to the whole world.

However, the novels of Victor Hugo are as much of an anomaly as the legend of the man. To judge Les Travailleurs de la mer or Les Miserables by the standards of the French realist novel from Balzac to Zola is to miss the surprisingly modern nature of his fiction making, which undermines the subject, using character and plot to achieve the effects of a visionary prose narrative. Hugo is as far removed from Stendhal’s self-conscious and ironic lyricism as he is from Flaubert’s obsessive concern for tight construction and technical mastery. The dramatic and psychological power of Hugo’s novels depends in large part on the creation of archetypal figures. Their poetic and thematic unity derives from his ability to conceive the linguistic analogue for larger forces at work. The sweep of his texts and the moving, even the haunting visions they project are a function of the widest range of rhetorical virtuosity.

Feature Image Credits: Mental Floss

Nikhil Kumar