The following piece seeks to present yet another easily dismissive view (read rant) of a Muslim in India. All names, people and incidents mentioned are NOT fictitious. Resemblance to any past event of dictatorship and fascism is NOT AT ALL coincidental. Any attempt to debase the piece as “anti-national” comes from a shrouded majoritarian privilege.

Few days back while I was flipping through the memories laden pages of my eleventh standard Political Science NCERT textbook revelling on the old nostalgia, I chanced upon Faiz Ahmed Faiz lines in one of the cartoons.

Hum to thahre ajnabi kitni mulakato ke baad

Khoon ke dhabbe dhulenge kitni barsaaton ke baad

(We remain strangers even after so many meetings

Blood stains remain even after so many rains.)

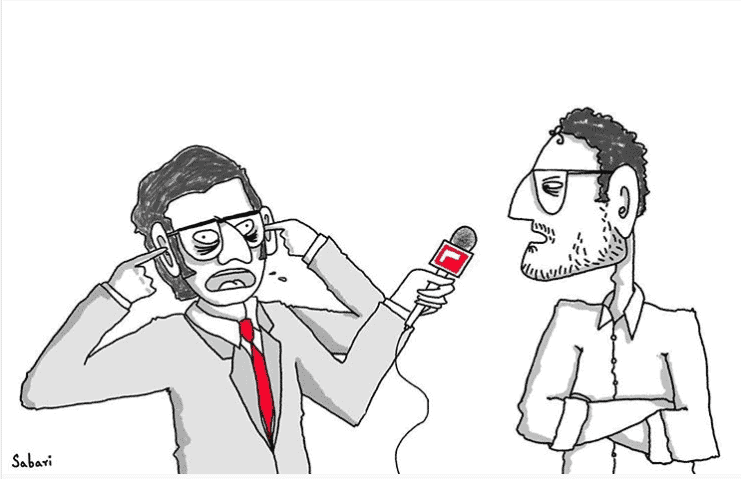

Indeed, the ongoing insurgency of our once dear democracy in the hands of the incumbent government gave new meanings to these lines. It is a known fact that the constant othering of the Muslims and other minorities has been normalised and conveniently subsumed in the state apparatus in the recent years. This manufacturing of hatred by the ruling party is certainly not a new phenomenon, but the extent to which it is practiced is certainly something that cannot be easily dismissed. The dehumanisation and humiliation experienced by certain sections of the people, especially religious minorities, cannot be easily language-d.

An imam stabbed and shot to death in a mosque that was burnt to the ground. A young doctor, walking home, set upon by an armed mob who thrashed and molested her. A teacher asked a kid to slap his classmate. An MP ridiculing another MP “terrorist” and hurling dehumanising slurs in the Indian Parliament. The incidents which took place in India over the last few months (and are increasingly a common sight), are seemingly unconnected, yet the victims were united by a common factor: they are all Muslims.

“In the early days of my college, in a class of 80+ students, my friend who was sitting beside me and I were made to stand up, our identities assumed because we were wearing hijab and asked by one of our senior professor, in a very condescending tone, if we ever faced discrimination in India,”

-a second year student of Delhi University.

A socially identifiable Muslim that fits in the perfect imagination of a stereotypical archetype is often seen at odds with the usual surroundings–worthy of suspicion, stares and second looks. In times of blatant and unapologetic Hindutva outfit of the government, practicing religion in public has become an increasingly dangerous exercise. A burkha donned lady is more carefully and suspiciously frisked at the metro station so does a cap wearing long bearded Muslim is exoticised and immediately seen as out of the place. Last month, when the violence against Muslims broke down in several parts of the country, I remember my father telling me that he has removed the hanging from his car’s rear-view mirror that had the verses of Qur’an written on it, as a step towards “precaution”. Muslim families are increasingly moving towards, what they consider, “religious neutral” names like Alia, Amir, Ayesha etc. to avoid being outrightly identified as Muslims. People avoid putting nameplates on their front doors for the fear of becoming targets of Hindutva outfits in the next communal violence. In such a political environment of Right-wing extremism, the public practice of religion for the minorities is becoming difficult day by day.

Another second year student who wishes to remain anonymous expressed her grief,

“I see way too many people than I’d like, defending violence against Muslims by turning the table and just blaming the Muslims for committing the violence themselves. Most of the times it’s my acquaintances or even friends; it makes me wonder how they actually perceive me.”

Being an ordinary Muslim in India involves waking up to at least one Islamophobic news and then for the rest of the day dissimulating your own identity for the fear of being identified. After a point our identities are just subsumed in the mere everydayness of these stories of discrimination and violence. The identity of a Muslim is battered against the social realities of the present systemic state oppression and is mutilated every single day–the vilified hypersexual outlook of Muslims that feed into the insecurity of the hyper-masculine Hindutva narrative of the nationalist discourse. The ritualistic nature of endless and unresponsive humiliation has led to conscious effort to not socially “appear as Muslims”; running away from our own identities. Will an ‘Indian Muslim’ continue to be an oxymoron? How long will our words of endearment—ammi, abbu, bhaijan, aapa will be misappropriated to give perverse connotations? How long our citizenship questioned, our identities thwarted, our cultures denigrated and our existence diminished? Maybe in the end of the day, what remains is the tiredness and a helpless resignation when we are questioned and made to question ourselves—who are we?

Read Also: Islamophobia in Delhi University’s Student Community: A myth or Reality?

Image credit: The Indian Express

Samra Iqbal