This International Men’s Day, let us dig deep into the social construct of toxic masculinity, and how women, knowingly or unknowingly, contribute to it.

Masculinity, as a concept and a reality, has evolved into much more than what it used to be years ago. Scholars have drawn attention to the fact that ideas of masculinity are tied less to the body and more to socio-cultural ideologies and practices. Masculinity, as an ideal, is not naturally given, but is a social construct with different parameters of fulfilment. To be born a boy is considered a privilege, but one that can be lost if one is not properly initiated into masculine practices. Besides, male adults must maintain this privilege through regular performance.

Emphasising on the privilege given to men, it is a position of power, and we often consider this position viable when there is a clear depiction of that power. This power expects men to be dominating, aggressive in bed and beyond it, and violent. History is witness that the supporters of this power are often women – women who have internalised this concept in the name of culture and habit, and then preach it, or women who just do not speak against it. Toxic masculinity is not a man’s issue, it is a societal one.

We have all been raised with these fascinating stories narrated by our grandmothers, such as The Mahabharata and The Ramayana. While these have been revered as holy texts, these books are not direct connections to God, but just tools of internalisation of wrong expectations and pseudo-spirituality. In the popular dicing scene, Draupadi, after her harassment, questions how she can be harassed, not because she is a woman, but because she is the daughter of a renowned king, Drupad, indicating how women are just property, first of their father’s and then their husband’s. On the other hand, Sita is often pedestalised and widely celebrated for never questioning her husband. These texts which are taught at universities, schools, and even in households have created unjustified expectations for men and lack of individuality among women.

After talking to a series of women on the ideals of toxic masculinity, one realises that often these ideals are perpetrated by women, especially in our Indian households. These women have gained the limited positions of power by being Maamis, Chachis (maternal and paternal aunts), Nanis (maternal grandmother), or even mothers.

One of the students, on the condition of anonymity, said that it was not his father who told him that boys don’t cry. It was his mother. A full childhood, the student said, of being told to suck it up and brush it off, to take it all in but never let any of it out. In the recent movement of speaking against toxic masculinity, a man wrote about his wife, how he loved her, how she often cried in front of him, how the one time he had cried in front of her, she had uneasily left the room, how he had made sure to never cry again, and how he did not know if his tear ducts even worked anymore.

One of the great things about the popularity of The Handmaid’s Tale last year was the arrival of a useful shorthand term: Aunt Lydias. Aunt Lydias are women who willingly, harmfully participate in a terrible misogynistic society. Aunt Lydias are real. Aunt Lydias are why toxic masculinity is a societal problem. I have heard the term “boys will be boys” thrown around by a mother at a parent-teacher conference, justifying why their son attacked other boys or lifted up girls’ skirts. “He’s just pulling your hair because he likes you” is something female grade-school teachers have been repeating for years. Especially when Indian primary education is dominated by female teachers, it harms girls by making them think unwanted attention is their fault, and it harms boys by making them think that harassment and affection are the same thing.

Sadly, the first person to tell me I was “asking for it” was not a man, but my own aunt. If we all really want to find a solution to eliminate toxic masculinity, it has to be against the individuals propping up the institution.

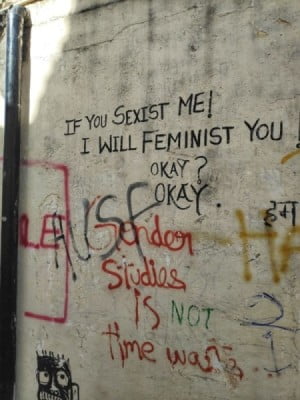

Feature Image Credits: Kartik Chauhan for DU Beat

Chhavi Bahmba