“Maybe there is a way to climb above everything, some special ladder or insight, some optical vantage point that allows a clear, unobstructed view of things. Maybe this way of seeing comes naturally to some people. Maybe if I’d been someone else I’d see it differently. But isn’t that the crux of the problem? Wouldn’t we all act differently if we were someone else?”

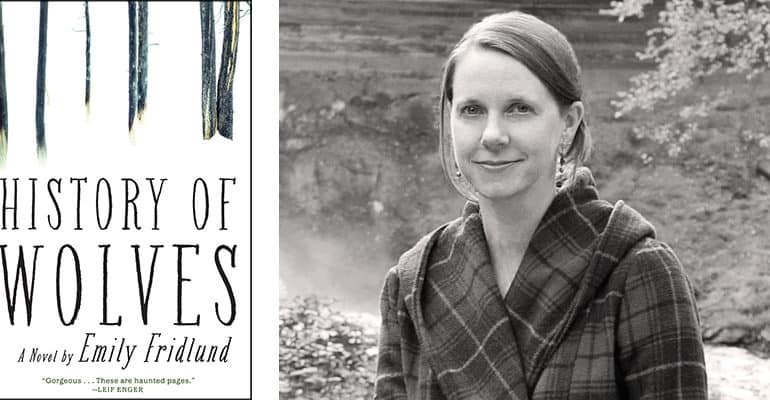

The crisis of coming-of-age identity and the adult world’s inherent debacle over thinking and doing forms the central motif in History of Wolves, the debut novel by Emily Fridlund and one of the six Man Booker Prize shortlisted novels of 2017. Quite certainly a more literally and thematically complex read compared to its competitors for the coveted prize, the initial storytelling and the ability of the author to paint detailed pictures even in an economy of words stands out while her inability to bring any substantial coherence to the plot devices disappoints.

The novel is narrated from the perspective of now adult, but primarily a socially outcast girl in Madeline Furston, also known as ‘Linda’ or ‘Freak’ or ‘Commie’ by her classmates. Her quest of self centres around her new neighbours in an otherwise secluded and disturbed upbringing in a lakeside commune in Northern Minnesota which later develops in her teenage experiences with her newly appointed history teacher Mr. Grierson and her classmate Lily. Throughout the text, the storyline traces its path notoriously meandering across time and space, expanding from her childhood days to her life as a grown-up adult leaving the reader with multiple interpretations of how things turn out to be.

Every page of the book is overpowering, leaving the reader with chills running down the spine and a feeling that something bad is going to happen. So powerful is the narration that an icy, soul-wrenching gust of air seems to blow throughout, and so grim is the dark and wintery portrayal of the geographical diameters of Linda and her school that the tale feels almost haunted. The treatment of the characters is powerful. Even for their grey underlined side which is always distinct, the reader is forced to sympathise with their paralysing loneliness, but the author invariably creates an emotional remoteness which prevents any emotion in a reader other than cold sympathy. That said, the remote plotline and the author’s inability to bring to a sensible closure the various parallel story strands leave the reader invariably dissatisfied and sad.

History of Wolves does not fail to retain the tension of the plot, making the readers frantically turn the pages and identify the scandalous restlessness building up in their hearts, but the disappointing coda makes the novel fall yards short of greatness. Nevertheless, the promising abilities which Fridlund exhibits in coming up with an atypical coming-of-age thriller and retaining an almost unfailing control over her diverse characters and expansive and parallel storylines is sure to establish her as one of the most promising authors of our time.

Feature Image Credits: Powell’s Books

Nikhil Kumar

[email protected]