The ‘Prana Pratishtha’ celebration of Lord Ram in Ayodhya on January 22 has evoked varied responses across India. Its impact is particularly noticeable in educational institutions, where some colleges experienced joyous events while others faced instances of violence and police intervention. Amidst resistance and celebration, the article aims to explore the question of religion within educational spaces by examining diverse perspectives.

On January 22, Ayodhya celebrated the grand opening of the Ram Mandir, which was celebrated like a national festival. A celebratory vibe permeated both outdoor and digital areas as the streets were decked out in saffron and echoed with “Jai Shri Ram” chants. Temples and streets flourished in the festive mood, signifying a unique happy occasion for believers. To underscore the importance of the occasion, several state governments went a step further and declared holidays for businesses and educational institutions.

As New Delhi was rife with saffron flags and bhakti music on January 22nd, the merriment was shared by educational institutions alike in the centre. The grandeur of the ‘Prana Pratishtha’ festival was evident by the active participation of educational institutions, with some expressing support and others voicing opposition. This dual participation highlighted the complexities of sentiments that many, particularly younger generations, had about the occasion.

The celebrations demonstrated a dichotomy in how individuals perceived the event—whether it was seen as solely religious and legitimate or as part of a greater political agenda. This interplay of ideologies was displayed with enthusiasm by diverse student groups across various universities.

Prestigious colleges like IITs and IISC, Bengaluru were out in force for celebrations. A student group at IIT Kharagpur took out a procession in support of the inauguration of the temple, while IIT Delhi organised the Akhand Ramayana path, followed by a bhandara and deepotsava.

We’d been given a half-day, but then eventually the holiday extended up to being a full day. There were rallies from the main gate to another end of the campus, with many saffron flags.

-A Student from IIT-Delhi

In Ashoka University too, celebrations were observed through bhajan sandhya and pooja organised by students.

On Delhi University’s North Campus, festivities were observed at the Arts Faculty while candles were lit near the streets of Hanuman Mandir. The University of Delhi itself was shut for half a day until 2 p.m., according to the notification released by the authorities. Many such campuses across the country organised hawans, rallies, and even allowed the live telecast of ceremonies being held at Ayodhya.

In Shivaji College, University of Delhi, a student who was visiting the campus during the weekend for a debate tournament said,

Shivaji College had conducted an event with the campus being decorated with rangolis and diyas, as it set up a stage for live music performances and had visitors showing up.

This, however, is only one side of the story; many students expressed their disapproval and criticism, and not all student factions were in agreement with this kind of festive mood.

For instance, Fraternity Movement Jamia Millia Islamia organised a university-wide strike in remembrance of the Babri Masjid. “Boycott for Babri, Resistance is Remembrance,” said a post on X (previously Twitter) by the Fraternity Movement, along with a video of students protesting with posters of the Babri masjid. As the videos of the protest went viral, police forces were deployed outside the premises as precautionary measures.

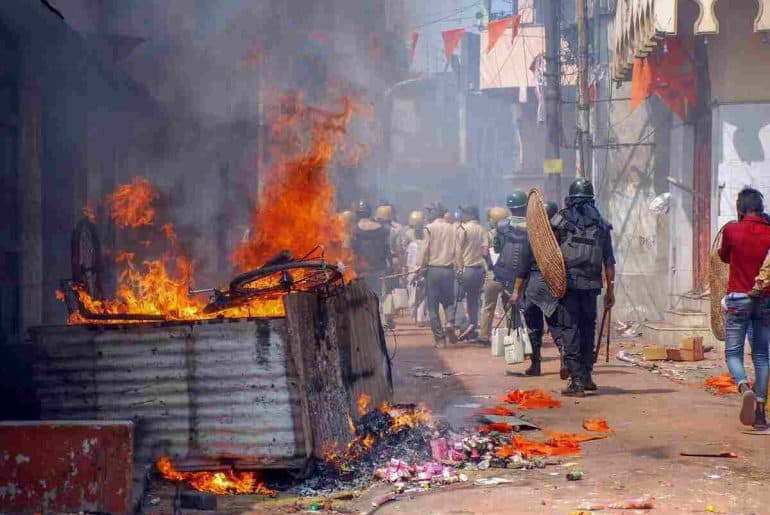

NIT Calicut’s students were forced to witness the cancellation of Thathva, their techno-management festival, which led to a stream of angry comments online. The festival was first postponed and then cancelled due to Central Security Agencies ordering the college after a student protested the Ram Mandir inaugural celebrations and was beaten up by the police, leaving no entity from the college with the power to intervene. Indignant NIT Calicut’s students’ comments read online, “Imagine all the work done by students to hear its cancellation due to a communal riot in the north.”

Tensions were also observed in Pune’s FTII (Film and Television Institute of India), where banners condemning the demolition of Babri masjid in 1992 were displayed with the statement ‘Remember Babri, Death of Constitution’. They took it a step further with the screening of the 1992 Anand Patwardhan documentary, “Ram Ke Naam.” The documentary delves into the communal violence that ensued after the Vishva Hindu Parishad campaigned to build a temple at the Babri Masjid site in Ayodhya. Additionally, they even invited Patwardhan on January 22nd for it.

However, according to a press statement released by the Students’ Association of the institute, chanting of the “Jai Shree Ram” slogan took place loudly outside the main gates, which the security was initially unresponsive to. Then, an agitated mob of 20–25 people entered the campus, and security was unable to contain them. Many students of FTII were brutally beaten up, and the banners were also damaged.

While the side of Samast Hindu Bandhav Samajik Sanstha, who was involved in the clash, claims that the move of FTII students was offensive to the sentiments of Hindus, provocative statements against Lord Ram merely created more rift amongst two religious groups. However, the students at FTII clearly see this violence as an attack on their democratic rights. They also claim that no action was taken towards the offenders, and they were allowed to roam free.

A post on Instagram describes the events that led to the violence at the FTII Campus, which involved the vandalism of college property and harm to students. The press release statement reads,

We appeal to the police and all relevant authorities to take prompt action against those who perpetrated violence against the students and who entered with the intent to vandalise property on the campus of FTII, Pune.

The student fraternity of ILS stands in solidarity with the Students’ Association of FTII and has even released a joint statement with signed signatures. Additionally, multiple students of FTII have released their own statement with signatures, demanding a response from Bollywood actor and Chairman of the Institute, R. Madhavan.

Similarly, in another college, the Indian Institution of Science and Research (ISSER), Pune, witnessed a distinctive response from certain students. Allegedly, on January 22nd, some students celebrated the temple’s inauguration in the campus common room. The movie club coordinator then planned the screening of Ram Ke Naam, sending details to students with a description of the movie copied from its IMDB review page. Unfortunately, this led to an unexpected turn of events, with policemen arriving at the campus. They questioned the movie club coordinator and, without clear justification, took them into custody. The move has left students at ISSER feeling intimidated by law enforcement, especially since they perceive a lack of support from the college administration.

Similar cases of violence and protest were observed in places like Jadavpur University and Hyderabad University.

In Hyderabad University, NSUI, which is the student wing of the Indian National Congress, organised a protest against the inauguration by intending to screen Anand Patwardhan’s documentary ‘Ram ke Naam’. The screening was disrupted by ABVP students, leading to its cancellation. The screening was later conducted peacefully at the North Ladies Hostel in the evening. Students in opposition state that campus spaces belong to everyone; hence, it’s their democratic right to express their concerns, and the screening of ‘Ram ke naam’ was a symbol of their resistance and not a step to offend people.

We ensured that organisations conducting their events went peacefully despite threats and attempts to disrupt by ABVP. Campus spaces belong to everyone; all ideas exist here. However, the administration and ABVP don’t want dissenting voices to be heard. The student community strongly opposed the saffronization of campus spaces; they attended in large numbers for SFI’s ‘Ram Ke Naam’,

-Md. Atheeq Ahmed, HCU Union President (source: Maktoob Media).

The unfolding of two contrasting scenarios in various universities prompts reflection on the democratic principles by which the country aspires to abide. The celebration of religious victories and moments in educational institutions raises a fundamental question about the integration of religion within these spaces.

We observed different celebrations, including bhandaras and rallies, where students enthusiastically chanted ‘Jai Shree Ram’ and danced.

Since religion is a very personal subject for me, I personally decided not to take part because I feel it is improper to hold large-scale religious festivities in colleges where you have such a diverse population. Students from minority groups experienced exclusion as well, and those who chose not to participate in the festivities were called anti-Hindus.

-A mass communication student from Madhya Pradesh described the events at her college.

She went on to say, “The decision to celebrate such moments should be left to individuals, and nobody should be placed in situations where they feel alienated in their own colleges.”

If institutions are justified in endorsing such events, does it imply that religion is an inherent part of educational institutions? If so, the ramifications in multi-religious countries like India are complex, as institutions should then consider accommodating the religious sentiments of each community rather than catering to the majority alone.

Would this extend to allow students from diverse communities to practice their religion within educational institutions through their own expressions of uniform, festivities, and prayers? If such practices become widespread, it raises concerns about their impact on student identity. Will the subject of religion either further divide them in spaces where they seek empowerment and education or provide them with greater freedom to embrace their individual selves?

Students are free to choose sides and voice their emotions, whether it be joy or dissent. However, carrying out religious activities in an educational setting is inappropriate and goes against the goal of the organisation, which is to safeguard students’ rights, interests, safety, and development. In these situations, political factions’ fuel for violence and conflict goes against both religious and constitutional norms.

-A second-year Delhi University history honours student

Through this, one can note that if educational institutions strive to maintain a secular nature, any form of religious exhibition contradicts their fundamental goal of providing education free from religious influences. At the same time, they must safeguard students from feelings of alienation or offence.

Can dissent coexist alongside the celebration of the auspicious arrival of Lord Ram? If one student group is allowed to express their joy, should others be hindered when they protest against it?

Lastly, considering religion is a personal matter for individuals, how appropriate is it to introduce it into educational institutions? Can our colleges and universities become safe spaces for discussions, education, and growth, free from the spectre of violence over religious differences? Can the youth liberate themselves from the constraints of rigid political and religious ideologies?

As we grapple with these questions amid both joy and turmoil, the answers lack uncertainty. The quest for meaningful resolution necessitates a delicate balance between respecting individual beliefs and nurturing an inclusive educational environment that promotes intellectual growth for all.

Read Also – Saffronisation of Cultural Expression

Image Credits – Bloomberg.com

DU Beat