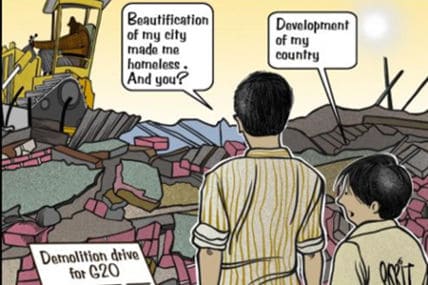

The following piece attempts to examine the roots of Hindutva ideology in India as well as the caste-class mobilisation on which it grows. In doing so, it will also look at the role of apolitical-centrist folks in fuelling fascism.

Fascism, as Time magazine describes it, is “a movement that promotes the idea of a forcibly monolithic, regimented nation under the control of an autocratic ruler.” Its origins can be traced to Europe in the early twentieth century, with Germany seeing one of the worst faces of that movement. However, after World War II, in 1945, fascism began to lose ground before resurfacing in the form of neo-fascism. However, fascism, unlike in the West, rose to prominence in India in the 1990s. Since then, fascism in India has grown to its worst, steadily choking the world’s greatest democracy to death.

In his paper titled ‘Neoliberalism and Fascism’, Prabhat Patnaik writes, “They (fascists leaders) invariably invoke acute hatred against some hapless minority groups, treating them as the ‘enemy within’ in a narrative of aggressive hyper nationalism, and attribute all the existing social ills of the ‘nation’ to the presence of such groups.” He goes on to explain in his research how these movements’ fundamental characteristics go beyond mere prejudice. It highlights the movement’s adherence to irrational viewpoints, desire for societal domination, and readiness to use violence openly—even in positions of governmental authority—in order to accomplish its goals. He describes the totalitarian tendencies of fascist governments as they attempt to dominate the social, political, and economic facets of society. This eventually leads to a highly controlled society in which the government has a significant influence over every element of an individual’s personal life.

Hindutva, also known as Hindu nationalism, is a fascist movement in India that advocates Hindu supremacy and the establishment of a Hindu Rashtra. This movement began in India in 1925, amid the fascist surge in the West, but received little attention from the public until the 1990s due to the dominance of a left-centrist political party in government. However, after the 1990s, the movement began to expand quickly, with the ‘Babri Masjid’ as the centre of the politicisation. The movement gained political traction with the formation of the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) in 1980, which was backed by the Rastriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP).

Dr Muhammad Gumnāmi for The Muslim 500 notes, “From the 1990s onwards, the slow poisoning of Hindu minds against Indian Muslims was carried out by the RSS and BJP. However, their progress to a majority with complete control did not occur immediately. The BJP passed through a stage where they had to form a coalition government under the ‘moderate’ Vajpayee, who was also an RSS member. The Vajpayee coalition government ran between 1998 and 2004, and while it was BJP-led, it did not have the majority to lay the foundations of a Hindu Hitlerian state.”

In a country where caste is severely established, Hindu unity was a challenging feat. At the same time, in the 1990s, the then-V.P. Singh’s government implemented the Mandal Commission, which granted 27% reservation to the OBCs. This policy was a political manoeuvre intended to harm the BJP’s electoral base by creating inter-caste divides. While most political parties stayed mute on the commission since any favour may result in them losing a specific caste vote, the RSS officially called on the BJP to reject the Mandal Commission. But the party used a different strategy to mobilise people and secure voter support. A month later, L.K. Advani, the then-BJP President, began the ‘Rath Yatra’ to promote the agenda of a temple under the Babri Masjid and deflect attention away from the Mandal Commission. From the start, the Yatra provoked sectarian tensions between Hindus and Muslims.

On 6 December, 1992, members of Hindutva organisations razed the centuries-old mosque, sparking one of the bloodiest communal clashes in the country. While the Hindu-Muslim gap was gradually deepening following the demolition, a train accident made it worse. In 2002, a train coming from Ayodhya caught fire, killing 58 Hindu pilgrims. This prompted violent riots in Gujarat, killing over 1,000 individuals, the majority of whom were Muslims. Many international organisations criticised the BJP administration, stating evidence that the violence had been planned and designed in advance. The inability of the state to control violence, acts of silencing journalists and critics, and banning documentaries make further cause for concern and question. From then until now, the BJP has been successful in uniting Hindus on the basis of hatred against Muslims.

A PhD candidate from the Centre for Social Studies at the University of Coimbra writes, “In India, fascism is reinventing itself. It has crept through Hindu nationalism—Hindutva—and now poses a serious threat to Indian democracy.” For the BJP, mobilising UC Hindus was an easy task. A fairly easy equation: Hindu Raj means Hindu domination, which means upper caste dominance. Along with that equation came the Mandal Commission, which eventually helped them acquire UC voter support due to open criticism from the RSS, the parent wing. In a poll analysis by Lokniti-CSDS, they reported that as many as 89% of Brahmins, 87% of Rajputs, and 83% of Baniyas voted for the BJP in the 2022 elections. The percentage was 66 for OBCs and 41 for SCs.

While the existence of the UC voter base is self-explanatory, the question arises: how did the BJP succeed in mobilising the lower caste? Their first card featured Narendra Modi. Modi has been quite aggressive about his caste identity since the beginning. The Press Trust of India reported, “Addressing a press conference at the JD(U) headquarters here, the party’s MLC and chief spokesperson, Neeraj Kumar, pointed out that Modi has been accused of getting his caste, ‘Modh Ghanchi’, included in the OBC list in 2002, when he was the chief minister of Gujarat. ‘Modi sought to deny the allegation by claiming it was done way back in 1994, when the Congress ruled Gujarat as well as the Centre’, added the JD(U) leader. Kumar showed a sheet of paper claiming it was the Gazette of India of that year, mentioning the casts that were included among Other Backward Classes (OBC).” A few other political groups also questioned his caste status, but the BJP successfully defended it by labelling the claims “casteist”.

Now the question remains: even after an increase in crime rates against Dalits since 2013, why are Dalits voting for the BJP? The answer lies in the class development of this caste. In the book ‘Maya Modi Azad: Dalit Politics in the Time of Hindutva,’ scholars Sudha Pai and Sajjan Kumar find out the reason behind this shift. The book explains how class upliftment is one of the reasons behind the shift in political support. Vikas Patnaik notes in his review of the book for The Hindu, “Indeed, this is one of the finest insights of the book. One sign of self-confidence is always fragmentation, as an individual or a sub-group agency begins to question the need for a larger ‘authentic’ self. Just as a Brahmin can be a supporter of the BJP, the Congress, or even a socialist, it goes without saying that a confident Dalit middle class will also articulate itself in fragments. In other words, the electoral debacle of the BSP also reflects the success of the BSP in providing ‘aatma-samman’ (self-respect) to Dalits who grew up seeing Kanshi Ram and Mayawati as their natural leaders.”

Another reason is the hierarchy within castes. An excerpt from Pai and Kumar’s book argues, “It is also because the objective has been two-fold: to obtain the electoral support required in a key state like UP and include them within the saffron fold in order to build a Hindu Rashtra. Feeling neglected within the BSP vis-à-vis the dominant Jatavs, the smaller Dalit sub-castes have been attracted to the BJP and thus rendered vulnerable to its mobilizational strategies.”

The BJP’s silence on the Mandal Commission, the addition of EWS reservation, RSS’ criticism of the Mandal Commission, weakening opposition, intra-caste dominance, and Modi’s identity were all enough to mobilise the communities and bring them under the banner of “Hindu,” with a common slogan, “Not a ‘Brahmin’, Not a ‘Kshatriya’, Not a ‘Vaishya’, Not a ‘Shudra’: We are Hindus.”

While the underprivileged lack access to proper education and information about issues, they vote with the hope that this can probably uplift their financial status, while the rich ensure that they stay ignorant and vote with hatred. As economist Prabhat Patnaik states, “Fascism has been thriving on weakening the working class across the world,” and indeed the present construction workers deal between India and Israel exemplifies that. In India, the BJP government’s control over media and internet platforms aids in mobilising the middle and upper classes. According to a recent World Economic Forum survey, India is the most vulnerable to misinformation and disinformation in the world, posing the greatest threat to the 2024 elections. The reason a lie becomes a fact in India is because the privileged either benefit from it or turn a blind eye to it.

Fascism thrives on the politicisation of religion, and misinformation to blur the distinction between political and religious events aids in the cultivation of an apolitical voter base that ignores socio-political issues. Such a voter base indirectly aids in mobilising the working class. A recent illustration of this is the violence that erupted in the country following the Ram Temple’s inauguration. While this voting base had the resources and access to education, they chose to remain in their bubble of privilege, thereby supporting the authoritarian regime and creating a religious gap in their personal relationships.

Furthermore, an analysis of how apolitical-centrist individuals unknowingly support fascism emphasises the importance of a nuanced understanding of political apathy and the potential consequences of being untouched by ideological shifts. The development of fascism highlights the importance of ideological neutrality in deciding a country’s political direction.

So, while we sit in our bubble of privilege, continue to preach hatred, directly or indirectly, and refuse to question the hatred, the regime will continue to divide everyone, incite riots, and fan the flame of hatred towards our doors.

Read also: “I am a Brahmin” The Casteism of Baba Ramdev and Shankaracharya

Featured Image Credits: Hindustan Times

Dhruv Bhati

[email protected]