With this review, we believe it is often important to revisit the classics as well!

What happens when you put 12 men in a small, claustrophobic jury room in New York during the hottest day of the year? It makes for an incredibly dramatic movie. ’12 Angry Men’ is a court room drama written by Reginald Rose, who is also the producer alongside Henry Fonda. The movie, under the direction of Sidney Lumet was made on an incredibly tight budget of $340,000 and its release in the year of 1957, although critically acclaimed, proved disastrous in the box office. It was only when it was aired on television that it finally found its audience becoming the classic it is today and deservingly so.

The Plot

An 18 year old boy is brought to trial for the murder of his father. All evidence finds him guilty; the jurors are convinced that it is going to be a really short session. But when the votes are called for, they realise that it is never that easy. One man out of all the 12 jurors is not entirely convinced that the boy is guilty. Juror 8 (Henry Fonda) is the only one to vote ‘not guilty’ in the preliminary tally and is the only one holding up a unanimous verdict. This infuriates the other jurors who want to get the session over with as soon as possible and resume their daily life. They try to convince him that he is over complicating the matter but Juror 8 stands firm in his belief that there is a room for a ‘reasonable doubt’.

Although the audience is given no preliminary knowledge of the case but as the story develops they are provided the evidence put in court in the form of third person narratives, as Juror 8 fanatically tries to argue the authenticity of the evidence. He believes that all the evidence is circumstantial and the boy deserves a fair deliberation. He becomes the only one standing between the boy and the electric chair. Human emotions flare as their patience is put to the test and the vilest of human character begins to surface as the discussion draws on. In the heated debate human values are brought to question, abuses exchanged and facts doubted. ’12 Angry Men’ brings to the screen human drama in its rawest state with all its prejudice, stereotypes and malice.

Casts and Characters

Sidney Lumet’s ’12 Angry men’ depends upon the volatile mix of personalities in the cramped up jury room to deliver a staggering courtroom drama. The jury members have their own way of life, their own personalities, and each one remarkably different from the other. The jury is a mix of common people from different walks of life – an assistant football coach who tries his best as the jury foreman (Martin Balsam), a meek banker (John Fielder) who is often dominated by others, an opinionated and short-tempered businessman (Lee J. Cobb), a rational and analytic man of facts (E.G.Marshall), A paramedic who grew up in a violent slum (Jack Klugman), A tough and respectful house painter (Edward Bins), A salesman (Jack Warden) whose only concern is the baseball tickets burning a hole in his pockets, An architect (Henry Fonda) who is at first the only dissenting voice in the jury, A wise and observant old man (Joseph Sweeney), A loudmouthed and prejudiced garage owner (Ed Begley), A European-born watchmaker (George Voskovec), A wise cracking advertising executive (Robert Webber).

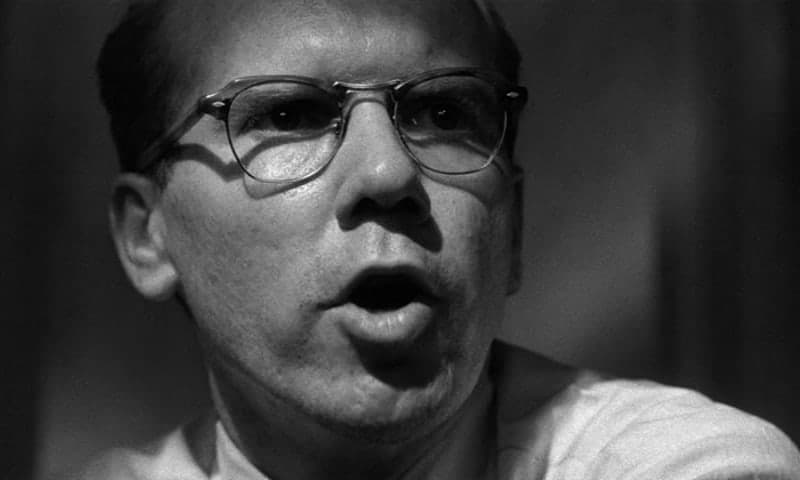

Each actor does a remarkable job in bringing up their character in the most believable manner. This becomes rather important as the film has a lot of close up shots of the characters. Every emotional outburst seems genuine and every argument carries such tension that can make you root for that one juror or make you pathetically hate the other.

Cinematography

’12 Angry Men’ is no Bollywood movie with enchanting Swiss landscapes where the characters seem to suddenly appear out of nowhere and burst into a song. Instead the movie is grim and almost entirely takes place in a small claustrophobic jury room. But this banal confinement becomes a completely dynamic set piece – when the audience gets one good look at the hot, tiny room with its confined walls, they are more able to empathise with the characters that are desperate to get the session over with. The room grows even hotter when twelve angry men throw their tantrums and their jibes as the walls seem to close in on them. The small room also becomes the silent representation of the jury’s narrow mindedness in the case in hand, a satire of ‘fair trial’.

Verdict

’12 Angry Men’ is a remarkable film. Although it does take time for the movie to develop but the audience will find their patience well rewarded in form of a thoroughly entertaining movie.

By Ambiso Tawsik ([email protected])