Schools and colleges are vastly different in many aspects, each with their own functions and purposes. Yet, could schools be better off in some way by imitating the institutions of higher education?

One of the most glaring contrasts between school and college that one experiences after stepping foot in the latter is the access to vast, almost limitless, freedom associated with it. Certain rules and regulations – hostel curfews and the like – notwithstanding, college majorly outshines school in terms of what a student can or can not do. From classes to clothing and attendance to activities and the rest, students are given numerous opportunities to experiment, explore and experience.

The mere agency that students have of visiting the stacked college libraries at their convenience or of listening to eminent speakers at some seminar is no small feat compared to the strict timetables and mechanical workings of a school. Consider how these resources can be used to develop oneself and you have a treasure trove of knowledge and learning, accessible almost entirely at will. Contrasting this with the fixed schedules, homework and mostly bookish education of school classrooms brings forth a rather grim picture.

This is not to say that schools don’t have a functional use or a practical purpose. It makes sense for a school to follow fixed daily timetables to instil qualities of punctuality in students, or to prescribe some homework so that students keep up with their studies, especially in their junior classes. But on the whole these features tend to become restrictive in nature, curbing creativity and freedom to no small extent and making students work within a closely regulated system.

Psychologist Peter Gray writes in Psychology Today, “Children hate school because in school they are not free. Joyful learning requires freedom”. In a separate article on the same platform, he further writes, “Children’s education is children’s responsibility, not ours. Only they can do it. The more we try to control it, the more we interfere”.

It’s common to watch children learn a multitude of skills and tasks simply by playing and experimenting. In many of the world’s most unique and innovative schools, like the Steve Jobs School in Amsterdam or the Green School in Bali, students are encouraged to choose what they want to learn and when in a model that stresses experiential learning.

However, the point of this article is not how teaching methods can be modernised but how schools can be made more liberal on a whole, most importantly in higher classes, say, from class ninth or tenth onwards. This would work out in three ways.

One, school students should be given greater freedom to choose how they want to attend classes. A more open timetable, which gives them the choice to experiment and alternate between classes on the one hand and library, club activities or workshops on the other will not only open up multifaceted opportunities of learning but also give the agency and responsibility of handling their own matters into the hands of the students. An argument can be made that students would become careless and stop attending classes in such a system. This comes from a highly paternalistic notion of how students should behave and the assumption that they can’t figure out what’s good for them. As long as this assumption exists, we won’t give agency and responsibility to students. Sure, not everyone would make the best use of this system. But even for that, the accountability would exist with the students – something that’s essential for an adult.

Two, more seminars, interactive sessions and discussions on academic topics or social issues by eminent speakers would not only expose students to important questions but also provide for a more holistic beyond-the-book education.

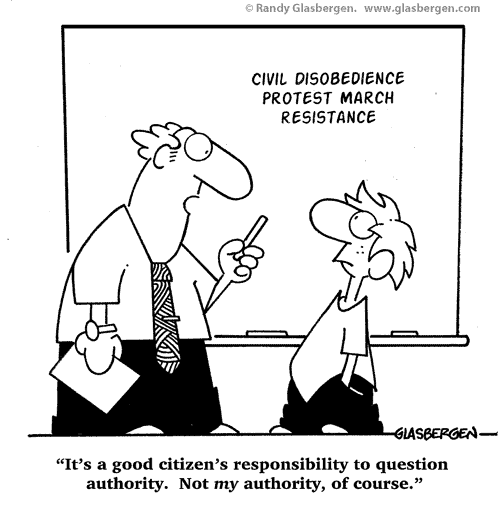

Third and perhaps most importantly, schools should be more political. This doesn’t mean that we need an ABVP or an NSUI in schools, but that a culture of democratic protests and discussions should be fostered. None of us has gone through school without facing a situation where we wanted to raise our voice, make some reasonable demands or show solidarity for a cause. Yet, what stops us is the fear of authoritative action. The threat of a suspension or a letter home is enough to deter dissent. Buttressed by feeble claims that students shouldn’t be engaged in politics and focus only on studies, schools are able to get away with unfair and sometimes frivolous rules and regulations. What is being envisioned here is not active politics per se, but the expression of dissent in a democratic manner, giving students an avenue to experience how authority, resistance and engagement work, for these are inescapable realities of life.

The preliminary step for all this is to make teacher-student hierarchies more equitable and balanced, such that students are not seen as subordinates who have to be kept under constant paternal guidance but active and equal players in the learning process, while teachers are not seen as commanding figures but coaches and team leaders who simply aid in the said process. At the core of this vision lies the freedom that Gray talks about.

“College environment is more flexible, there students are expected to take charge of their own education. Therefore they need to be mentally stable in order to make use of the flexibility and various opportunities available to them… (qualities) which they should have developed in the protective school environment”, says Ms Piya Narang, a teacher or History at Delhi’s Birla Vidya Niketan school.

Our opinion is that schools can foster better- prepared students by not keeping them sheltered but by exposing them to the one quality humans heavily desire – the state of being free.

Image credits – Glasbergen

Prateek Pankaj

[email protected]